"Cursed is ground for thy sake; in sorrow shall thou eat of it all the days of your life." Genesis

Get Drunk and Mow

1970s, I’m in the back of a Volvo stationwagon, probably unbuckled. I hear my Grandmother in the front seat, “They love to mow their lawns,” She says wistfully, “Get drunk and mow their lawns.”

Twenty years before Meema (who had her issues, God bless her) shared that particular nugget of wisdom, an Egyptian exchange student named Sayd Qutb was sent to Greeley, Colorado to study. Greeley was a sleepy little all-American town on the plains, but Qutb looked on it and saw something else.

“The owners of these houses spend their leisure time in toil, watering their private yards and trimming their gardens-- this is all they appear to do.”

Qutb was a troubled dude, whose alienation also manifested in disturbing sexual observations. But his comments on the American obsession with lawns would have made perfect sense to my grandmother. He continues…

The most important thing for these people is the tending of their gardens... there is nothing in the way of beauty or taste... it the machinery of organization.... devoid of spirituality and aesthetic enlightenment.

Sayd Qutb returned to Egypt, alienated from Western values, and joined the Muslim Brotherhood. He would go on to become what some refer to as “the Father of Al Qaeda.”

There’s something about lawns.

Qutb would have chuckled while reading Phil Roth's American Pastoral. It’s a story where an assimilated Jewish man (the “Swede") and his beauty-queen wife move to an idyllic horse farm with long sweeping lawns. He tries to provide his daughter with everything she could ever want in this WASPy fantasyland, but she rejects this way of life and becomes involved, Like Qutb, in extremist and violent political groups.

By now, there are many cliched versions of this story- the alienated Jewish person trapped behind a well-mannered suburban lawn. The Coen Brothers "A Serious Man" makes an entire movie out of these sort of cliches. Ha ha, we get it. But what is it about lawns that drives us crazy?

The Hoyf

Adaptations had to be made to a new order of life; learning how to take care of a lawn and cope with a "garden shop," fixing correctly the tonalities of suburban social life, discovering the softenings of opinion and voice that might be needed at a local school meeting and finding the kind of people with whom more could be shared than the accident of proximity.... From the World of Our Fathers, Irving Howe.

A clue to the answer comes in the form of the Yiddish word for lawn, "hoyf." Hoyf is an important and common word in Yiddish and it translates roughly to "courtyard." But the space between the lawn and the courtyard contains the heartbreak my Grandmother spoke of.

Eden: Our world begins in a courtyard. The prototypical garden in the Jewish imagination is the Garden in Eden. One curious feature of the Garden of Eden is that it is enclosed enough that it can be blocked by putting one angel with a flaming sword at the east. Later interpretations referred to it as a Paradise, or park of luxuries, similar to the Persian word for a luxurious and definitely walled space, which was Paradaida.

Hortus Conclusus: From Eden's walled paradise, the courtyard/garden takes several paths through history. In Islam, it took on a central role:

Since Muhammad's followers would gather at his home for prayer, the side of the courtyard facing the qibla, or the direction of prayer, included a porch covered by palm branches, which offered shelter from the hot desert sun. Most early mosques, as well as the majority of later mosques in Arab lands, follow this general layout.

Socrates' also taught in the shade, the famous olive grove Socrates squatted on that belonged to Akademos. This space was semi-public, and did not have walls. But it would soon grow them:

The trend would continue in the West, regardless of religious differences between pagan and Christian, as sacred spaces were slowly controlled and centralized by a priestly class. This change in architecture reflects the larger change in spirituality as it began to be restricted, monopolized and made indoors by that same priestly class.

In the middle ages, the hortus conclusus emerges as a refuge (the original olive grove of the Greeks was also one of literal asylum, a concept that may have Ancient Hebrew roots as well), somewhere between inside and outside and somewhere between sacred and profane. Its influences are Roman as well of Christian or Pre-Christian. I have to be brief here and elide over some fascinating history (the wiki is surprisingly good for this), because we have a lot to get to.

The Jewish Courtyard

The few sources we have seem to imply the more modern Yiddish "hoyf" has its roots deep in the medieval era.

In crowded medieval cities such as Toldeo, Barcelona or Gerona, houses were more than one story... often a shop would occupy the first floor, with the family living above it. In contrast, homes in Muslim cities, such as Cordoba, Seville or Granada had courtyards, fountains and gardens.... some wealthier Jews in Toledo also had courtyards and gardens. Daily Life of Jews in the Middle Ages

Private courtyards were a luxury, a sign of wealth, as they were in the private interior gardens of Rome. More common were shared courtyards. In Eastern Europe, Jews would often live in two story dwellings and have the first floor work as a market space and be open to the public. Their courtyards weren't in their homes but, either in shared spaces or, like the Christian hortus conclusi, in semi-religious spaces.

The Shulhoyf

The big courtyards where people gathered were in front of the synagogue. These shulhoyfs were very important public spaces as can be imagined. But by now, the meaning of hoyf is veering quite a bit from “lawn.” What and where are hoyfs?

Courtyards refer both to the spaces between houses, where the inhabitants of the surrounding dwellings interact with each other, and collectively, to the surrounding structures themselves together with the space between them. Zelmenyaners, M. Kulbak

What wasn't a hoyf then?! Hoyfs, in the sense Kulbak used them above were becoming public or semi-public spaces, where people were expected to be social beings.

Let's take a look at some examples to see how this works:

Shloyme's Courtyard

Near their house grew four beautiful trees, and a large bench stood under them. My mother and uncle loved to sit there with their friends. At the windows of the house there were wooden shutters that were closed and locked at night with hooks.... In every Jewish courtyard was a cellar for storing vegetables, fruits, and barrels of good Moldavian wine. from Jewish Life in Bessarabia Through the Lens of Shtetl Kaushany by Yefim A. Kogan

Actors and Musicians

I remember that we lived on a courtyard that was like a box. Although it was a big industrial city, our courtyard was like a little shtetl. I knew a lot of children who lived next to the courtyard. We played blind man's bluff. And various magicians, actors and musicians used to come to our courtyard. And I remember we sang Gertibig's songs in our courtyard. From Memories of Pre-War Lodz Moshe Sachar

Vilna Shulhoyf

At its center was the shulhoyf, a courtyard complex that boasted the Great Synagogue, many smaller prayer houses, several communal institutions, a public bathhouse and old well and a clock marking the time for prayer. The shulhoyf's more traditional spaces later competed with those that attempted to bridge the divide between observant and modern Jews, such as the Strashu Library... by the interwar period the area was also a hangout for local toughs, actors, and writers, many of whom congregated in bohemian spaces like Fania Lewando's vegetarian restaurant and the neighboring Velke's cafe. From Vilna My Vilna by A. Karpinowitz.

Pre-WW2 Odessa Courtyard

The courtyard was very unique. There were two categories of people. First, there were those who worked for the Jewish Funeral Brotherhood which was located in our building... the second category was workers. Many worked in the port as stevedores... A stevedore never drank vodka with anyone from the Funeral Brotherhood. They said, "They eat their bread from others' grief."

The composition of the courtyard was very international. Among my friend there were Greeks, Germans and Bulgarians... In courtyards, people for the most part lived on friendly terms. I don't remember serious scandals with the exception of those times when one of then stevedores came home very drunk." from Viktor Feldman, quouted in Richardson's The Place(s) of Moldovanka in the Making of Odessa.

The Capital and the Province

More than a hundred years ago it was remarked that Odessa had the charms of both the capital and the province. Her streets are like the capital and the courtyards like the province. From Elelna Karakina

Pajamas

Courtyard residents always considered the courtyard part of their home. That's why it was acceptable for women to go around in a housecoat and men in pajamas...because everyone knew each other, the resident of old courtyards hardly ever had curtains in the their windows. Everything would become known anyway. From Anna Kerpel in Richardson, ibid.

Children's Paradise

The courtyard was the Jewish children's paradise... the air was filled with the voices and noises from the morning until dark, except in a frost or rain or sabbath. Children, younger or older, richer or poorer, kept busy playing all kinds of games. For some children the courtyard was the only "outdoors" where they had space to move and air to breathe...the courtyard was also a school of life for the Jewish children, the Moyselach, Surelach, Yoselach or Lealach. It has been a microcosm of Jewish Life in all its aspects. many generations of Jews went through this "school" carrying with the nostalgic memories of their childhood. From Israel Bernbaum

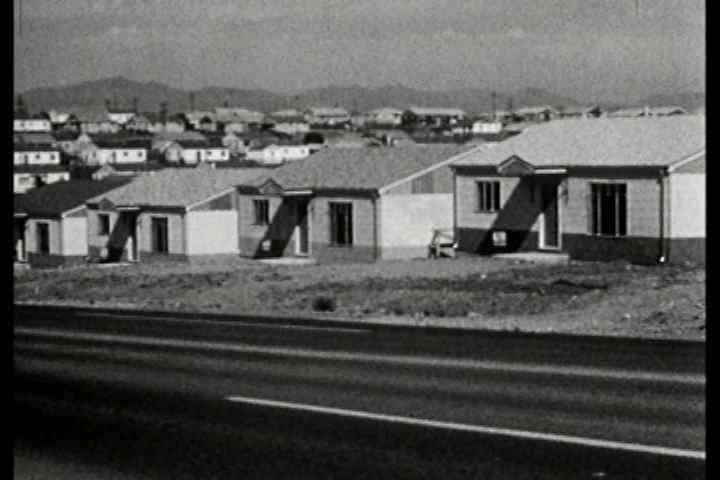

I could go on and on but you get the idea. Now imagine coming from this world to America, where the lawn is manicured perfectly but expected not to be the site of social life, but a barrier to it. Janisse Ray, in her brilliant Ecology of a Cracker Childhood, explains how lawns and green spaces were, in part, meant as a security buffer to the Scots-Irish descendant folks in her family. In their imagination, shady trees were not seen, as they were by Mohammed or Socrates, as a nice place to hang out, but as obstacles to a long view that decreased their ability to defend themselves. To my grandmother and to Sayd Qutb, those lawns were every birthday party they were never invited to.

Coming Next: Ghettos and Capitalism, The Demise of the Courtyard and the Practical Considerations for a Science of "Psychic Courtyardism."