…and it's easier than it looks.

There are two main ways to play klezmer songs on diatonic harmonica and they are very different. One is very technical, very melodically complex and kinda hard to do. I call this the “Fancy Method.” This method’s foremost practitioner is probably Jason Rosenblatt. Truly lovely.

The other method is a lot easier but still very fun and has plenty of room for artistic expression. It even has important implications which get to the heart of klezmer and Psychic Courtyardism©. I call it the “Old-Time Method.”

Both methods are wonderful and have advantages and disadvantages. This post is about the Old-Time Method. I’m not an expert on this method. I started too late in life with too little talent, but some whippersnapper could do a lot with it, and maybe I’ll get a chance to play with you sometime!

The Old-Time Method uses minor-tuned harps which give us most of the notes we need without having to bend them. I call it Old-Time because it uses techniques pioneered by so called “old-time” and blues musicians, who really explored the full range of possibilities in this style.

Find the Notes

To start, get a G harmonic minor harmonica (not natural minor- I recommend Hohner or Seydel. I’ve never tried Lee Oskar but am told they work good enough.)

G minor?? But I thought klezmer was famous for being in D??

Well, if you look at these notes, you'll notice that the notes for D freygish can be found in two octaves. And, it even has the chords (Dmajor, Gminor, Cminor) to go with it. To get the complete D Freygish mode, you just have to bend two notes, 3 draw (way down to Eb) and 2 draw (down to C and occasionally B- use your belly!) It will take some time to do that, but it is possible, and there are lots of great videos teaching you how to bend notes. Once you get that, you can unlock a ton of freygish tunes.

But what about the minor chord tunes? In these cases, I still like the G minor harmonica. Why G minor instead of D, which is a more common key? Since the Old-Time style is conducive to playing solo or with minimal accompaniment (see video below), playing Dm tunes in the key of Gm is not much of a problem. Chances are you won’t have another musicians who needs to transpose and your audience won’t know what key you’re playing in anyway.

Ok but why G? On harmonica, I prefer the lower Gm register as it is a little easier on the ears. If you really, really want D minor, then go ahead and buy you one (you’ll also be able to play in a piercing A Freygish on those.) The D minor’s high pitch is great for cutting through a large ensemble, but a little squeaky when played solo.

Once you can play those two modes comfortably, you’ll notice Misheberach in Cm is also possible, but a little trickier and with less chordal support. And all this fits easily in your pocket.

Rhythm and Chords

This style has one huge advantage (besides being easier to learn). The Fancy Method can play gorgeous single-note melodies, but those notes can sound a little lonely without harmonic accompaniment (to get around this, for example, Jason plays piano and harmonica at the same time- nice but a little awkward).

But with the Old-Time method, the individual notes don’t require such precise embrochure, which means you can play single note melodies as well as multi-note harmonies…. at the same time. Here are the chords, and partial chords, you can play on a G harmonic minor harmonica.

How? By using a technique disgustingly called tongue-blocking, you can play melody and chordal accompaniment together.

And this then unlocks a third thing- since you’re playing melody and harmony by yourself, you can now control the rhythm and arrangement as well. Note how in this piece (slightly sped up- long story), I’m able to arbitrarily control the rhythm and even stretch out wildly for “expressive effect” whenever I want.

And because I can play accompaniement without a band, I don’t have to worry about communicating these wild on-the-fly aberrations of time and space to others.

Ornaments

The better Fancy Method players are able to play very soulfully with lots of ornament. But I find that the extreme bending they have to do sometimes requires a pucker approach (as opposed to tongue-blocking) which, to me at least, makes some useful ornaments hard or maybe even impossible.

One benefit of the tongue-blocking method is the famous “tongue slap” which unlocks a common klezmer ornament where a lower note quickly precedes the main note. In the key of G minor, a lower D might quickly precede a G, the G precedes a Bb, etc.

This itself is a huge aid to making melodies more ornate, but if you combine that with a very fast head shake, you can get add an upper super-quick “ghost” note before finally landing on the main note- lower, higher, main. your basic krekht. I’ve played them better before and will probably edit this later with a better version, but here’s my best take this morning, you get the idea:

Slides and bends are virtually synonymous with harmonica and easy to do. Blues bends tend to go up where klezmer bends go any ol’ whichaway. Trills are possible- sorta. We call it "warbling" in harmonica-ese, and its one limitation is that the two notes in the trill aren't close together like they usually are in klezmer. Bummer. Instead of say a D/Eb trill, we have to settle for either D/G or even something like A/C. Awkward, and not historically accurate, but the gritty tone of the harmonica makes it more satisfying than it sounds. You can see me try some here over Mark Rubin playing the banjo or just listen here (:28 secs in, also featuring my bones debut):

Finally, I find playing instruments not in the core organology of klezmer to be liberating. It allows me to focus more on phrasing and rhythm and expression. And yet, these “modern” instruments did exist historically, although marginally and briefly. Joel Rubin’s grandfather played open tuned guitars and Cookie Segelstein’s kin (father?) played Jewish tunes on the harmonica. Unfortunately, this last wave of organology coincided with a major collapse of this music in general. I think of playing the guitar and harmonica as an exercise of “what might have been.”

The harmonica seems to fit in naturally with string instruments like guitar and banjo, in a way klezmer fiddle can’t (or hasn’t yet), and may have a role in adapting klezmer to these post-trad contexts.

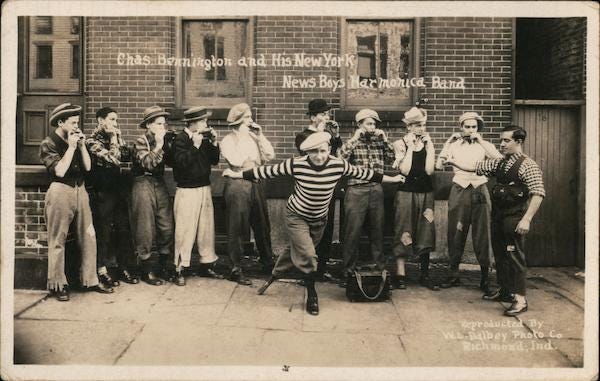

There is a fabulous story of a couple of Jewish virtuouso harmonica-playing kids, Ben Kassover and Isidore Greenblatt, competing up and down the East Coast in the 20s' with some other colorful characters. Would make a great movie or a book by (RIP) Paul Auster. Pat Missin tells the story and includes a great photo. I’ll let him tell it (see his addendum). Kassover recorded one (risqué) tune which I think has never been unearthed, and with the amazing banjoist Harry Reser, but this is another version of it,

Accepting Limitations / Psychic Courtyardism©

The harmonica's portability and ability to play single or multiple notes makes it superfun. But it has limitations! And that’s a good thing.

The biggest limitation with this style is that you can't play everything! That isn't the point of this style. You can play enough tunes with enough variety so that you can entertain yourself and others for long enough.

Since our culture tends to overemphasize melody as being virtuously synonymous with music, we often think the more melodies you can master, or the more melodically you can play, the better. This was even a key distinction between the two strains of klezmorim, the elite strain, who could play beyond the genre and were often musically literate and the “lowest of the low,” who could “only” play klezmer (and yet somehow had something special the others didn’t.)

But I’m encouraged by the example of Joe Thompson, an African American fiddler from North Carolina, and other old-time and blues musicians, who used to play all night long even though their repertoires were quite limited. Nowadays, we have a gazillion tunes at our fingertips but get bored after an hour. What if music had other goals besides more and more melody?

Also, this is a great technique for those intimidated by clarinets and accordions and complicated sheet music. Heck, the dang thing practically plays itself in G minor once you get the tounge-blocking thing down, which in itself isn’t very hard. It’s a great, inexpensive way for lots of everyday people to explore music (the horror!)

Also, one more thing! This genre “old time klezmer harmonica” is very possibly entirely invented. There is no evidence anyone used harmonica to play klezmer in quite this way in the “authentic” past. More likely they played religious niggunim or theater songs. As always, we here at Psychic Courtyardism© are fine with fakelore in the service of conviviality.

Playing With Others

There are many tunes you can play completely in this style, but there are many, esp those with lots of chromatic passages, that you just can’t. In between those two poles, there are a whole bunch of tunes that you can play partially. For instance, lots of tunes have a major section that might throw you for a loop (unless you switch harmonicas quickly). But don’t despair! Even though you can’t play them solo, you can play these tunes with others. In those cases, I let the other players handle the parts I can’t play and use the advantages this style provides to do something besides melody, which gets tiresome after a while anyway. Chug on chords, wail on a warble, play bass note(s), clap, pull a bird whistle or rhythm bones out of your pocket, whoop, sing a funny lyric, dance, rock the badkhen hype-man thing, or consider the unthinkable- lay out!

Here’s a Video

Not trying to toot my own harp here, but this is a demonstration of how the harmonica and guitar don’t have to be umbilically tied together for every single note forever and ever, but can add color, tone or antiphony.