Recap

In trying to find your own music, you might open a book of klezmer melodies, only to be told by the experts that the real essence of the music lies in the ornaments. But while learning those, you come across old-timers who say the ornaments are over-emphasized, or as Cookie Segelstein's European kin pointed out, that some "essential" ornaments like krekhts, were entirely a product of specific regions and time periods and were not reflective of any pan-Yiddish style. The old timers instead spoke wistfully about something called "phrasing", but upon trying to learn about that you find that no one says much of anything about it, aside from some crucial contributions from Josh Horowitz and Joel Rubin.

But why all this fuss about phrasing? The meaning becomes clear when we find the same elements of phrasing in the realm of gesture and dance. In that world, it is easier to see the important social dynamics that phrasing and gesture serve and which distinguish klezmer from so many other types of folk or social music. (see previous posts)

Jesters

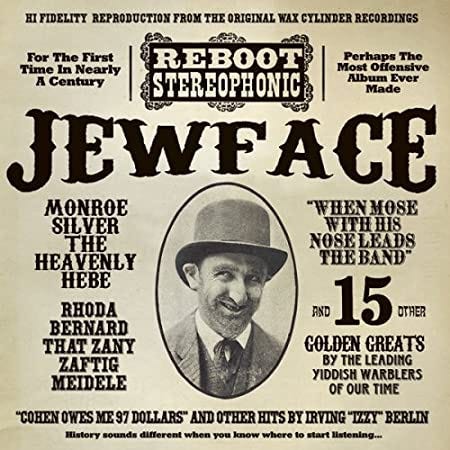

Gesture and Jester are etymologically related, but I'm not gonna start this post with "Webster's defines Jesters as..." A simple image will suffice:

Sendrey sees in this depiction of a Jewish entertainer evidence of "wild" hand gestures and although Susskind of Trimberg can’t be called a comedian, (his songs were actually a bit on the morbid side), he will have to represent for us those generations of pre-klezmer entertainers, clowns, letsonim, marshaliks, etc. who rambled through various courts and towns looking to try out their act.

We know so little about these folks. But one of the folks who poked into it, Walter Salmen, draws a conclusion similar to the one we saw in the previous post:

Itinerant singers did not want to hold monologues, without a reaction from the audience but rather to enter whenever possible into an exchange with enthusiastic listeners and elicit their active participation. (Rubin)

This reinforces the notion we saw before that the music had a social relationship with the audience. And to this end, jesters used gestures. This quote comes from the 20th century, but I think it applies:

Jewish Jokes, in print, are properly speaking, incomplete. They should really be heard and seen. Their communication is not only verbal. The gestures and the facial expressions, the rise and fall of the voice of the storyteller, are essential parts of the telling (Theodor Reik via Dauber's Jewish Comedy: A Serious History)

This image, and the Salmen quote, are more poetry than hardcore evidence, but it's all I got. Plus it's a lovely place to start- a unitary world of music, entertainment, gesture all tied together by the desire to create "active participation" between performer and the audience.

This unitary world would soon fracture into two figures, the klezmer and the badkhn, although the desire to engage actively with the audience would only become more pronounced with this change. The badkhn's job was essentially theatrical, he was trying to move you. In secular form, he would become the actor or comedian, and would, along with their klezmer/musician counterparts, wind up on theater stages or 78 rpm records together. And this takes us to the 20th century.

Dialect

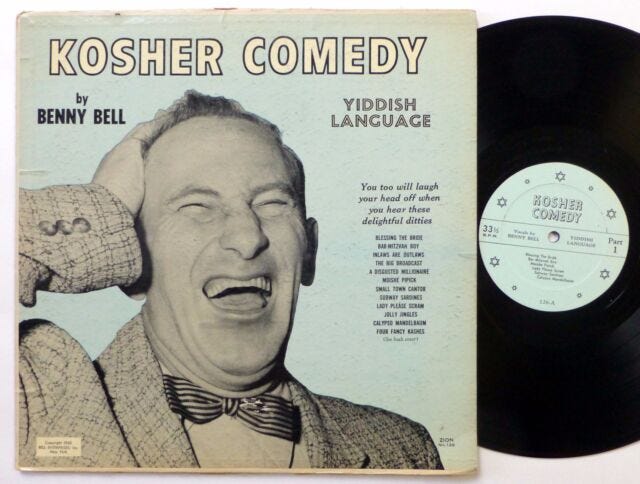

The old-timers, who sometimes gave you a funny look if you ornamented too much, seemed reluctant to discuss their unease. But in the world of comedy, they did talk about it. They used a word we don't see in music circles but which is very handy: dialect. A dialect comedian is one who talks "vit un" accent and plays the part of the new naive immigrant. The problem with dialect relates directly to what we saw previously with phrasing: the role of the audience.

I admit that in my own work I have deliberately expurgated dialect stories. I’ll tell you why, too. I was in the audience of a night club while a famous “dialectician” was regaling a predominantly Gentile audience with stories of shrewd Jewish businessmen, of fat and uncultured Jewish women in mink coats, stories of Jews who outwit Gentiles—and the audience howled. Their laughter frightened me. The entire scene recalled the Nazi beer hall where comedians with derby hats and beards told the same type of story to those who later were to become the executioners of our people. (Levenson)

This discomfort with dialect was especially felt after WWII, for obvious reasons. But not everyone agreed with it. Here’s Ben Hecht in 1944:

Out with the Jew has been the cry of his Simple Simon "well wishers," let no uncouth or satiric sight or sound of him be offered... He is safe now, the little Jew. No baggy pants, no over-sized derby jammed over his ears, no mispronunciations or waving of hands, the caricature has been wiped out...And with it is gone the open-heartedness, the quick sentimentality, the eagerness for fun, most of all this genius for fun- the half mad capering of irony and jest that is the oldest of Jewish tradition.

Hecht lost, and things changed. Although Mel Brooks had been doing his tame but dialect-inflected "2000 year old man" routine through the 50s in private, he didn't feel comfortable recording it until the 60s. But the writing was on the wall, Dialect was dead.

Phrasing vs. Dialect

The show must go on, and it did. Jews continued to perform and the late 50s/ early 60s saw an entirely new generation of recognizably Jewish entertainers, ranging from Woody Allen to Lenny Bruce (not to mention some absolutely insanely funny female comedians). They shunned dialect, but used an unmistakably Ashkenazic Jewish approach to phrasing. A few stayed with dialect, like Jackie Mason, who noted that it was Jews who complained that his act was "Too Jewish."

With the minstrelesque dialect gone, artists still were able to find and use a variety of phrasing styles. The distance between Bruce's staccato rhythm vs. Allen's whine vs. Larry David's exaggerated "nu?" legato is a nice sketch of the wide range of styles possible. Listen to that Chekhov's Band CD and think in terms of these styles. Ironically, removing dialect allowed for a wider range of expression. Dialect (which I'm equating to mechanically used ornament in case you haven't figured it out) is hopelessly two dimensional, while phrasing is a wide unknown variable, one that we're still discovering new ways to embody. Which is good news, since phrasing seems to last longer (“cultural retention” is the fancy word) than ornament:

Though modern Jewish humor is significantly different from the wit of early Yiddish dialect comedians like Benny Rubin and Menasha Skulnick, there are interesting similarities. Their voices may be silenced, but ... the cadence, phrasing and structure of the Jewish immigrants' speech have become familiar to our ears. Listen to the punch lines of the classic jokes... and hear the echoes of Yiddish...(Robert Menchin 101 Classic Jewish Jokes)

The best example of this today is Veretski Pass. If you compare the phrasing of Cookie, Josh and Stu you will notice something absolutely unique in the world of klezmer- they are all different. The "voices" have actual personalities. This is entirely missing in many other current klezmer bands, who, in their anxiety about playing accurately, are therefore mimicking a monolithic "style". It's probably not an accident that Josh's playing in particular, sometimes even approaches a complex form of bodily humor (listen to his fills on the German Goldenshteyn album.) But we need not literalize comedy, Cookie’s fierce seriousness and Stu’s curious mysticism are all equally valid.

So what can we make of it?

I'll show in the next post a pretty strange and beautiful response to this. But for now, I think we are forced to see that the motivations of jesters/gestures- the spontaneity, the desire to be open and honest, the desire to reach out and engage people- clash with the well-intentioned desire to use historically accurate ornament and phrasing. Most current klezmer playing is, even when it's perfect, in some sense dishonest, in a way that someone like my mother or someone else who came up in the tradition would be able to smell instantly (see Soloveitchek for more on this). This isn't a problem for other styles, like old-time, because they don't share the same assumptions about what performance is supposed to do. (Blues is a interesting example of something somewhere between the two).

Comedy represents an alternate path, where the same questions were wrestled with, but where different conclusions were reached. We have to remember that even though modern Jewish comedians deliberately eschew dialect as hacky, they are still very much putting on an act. It's a delicate balance. It has to be anchored in reality enough so the audience can suspend its disbelief, but exaggerated in just the right places so the humor becomes apparent.

I’m not saying it’s an easy comparison- Jewish comedians aren’t tasked with performing “Jewish Comedy” the same way klezmer musicians are tasked with playing “(Ashkenaz) Jewish music.” They have a freedom we don’t. But is there anything we can steal from their wild successes?

It may be easier than it looks. To paraphrase Kafka, "You know more Yiddish than you think." American Jews still have recognizable speech phrasing styles, even when they are very subtle. Even when they are not there, that's interesting too (where my Litvaks at!). All it takes is a slight change of focus to notice them. No need to exaggerate or cover up inadequacies, it's all perfect as it is. We just need permission to use it a bit theatrically.

Finally, like with the comedians, our phrasing styles are not even internally consistent. We switch codes all the time. To play in one style for an entire show is as phony as it is to play a show composed entirely of klezmer tunes, which as Josh Horowitz has rightly pointed out, is only found in the performances of modern revivalists. Instead of diluting its meaning, many secular Jewish folks claim the comedic worlds as an expression of their identity much more than pure klezmer music.

Let us also take inspiration from the comedy 78s where klezmer was interjected in fragmented forms. This is klezmer "in quotes", where a sufficient distance is interposed so that we can appreciate the form without having to pretend to be it. Veretski Pass also treads this line. While one senses they aren't afraid of "klezmer" (and occasionally pluck tunes from the core repertoire), they never use the term and they seem to intentionally keep distance from anything that could be considered an authentic performance of it.

Bottom line, just as gesture showed us the social aspects of phrasing, comedy illuminates a path to a creative relationship with phrasing devoid of ornament.

Next: Phrasing and Descent, Part 5: Irony & Jest

Afterword

Jeremy Dauber's Jewish Comedy: A Serious History is a great read and very illuminating.

More than other posts, I left a ton on the cutting room floor here. Specifically (oh no!) there is an interesting connection to be made between humor and the crisis of ornament that we saw in previous threads. Henri Bergson wrote an essay on Laughter in 1900 that makes an interesting connection between humor and the mechanical. As you recall, the mechanical poses a problem for ornament, because mass produced ornaments simply don’t work. Bergson sees the interaction between the mechanical and the human as a key component of humor, and he ties it together with gesture.

THE ATTITUDES, GESTURES AND MOVEMENTS OF THE HUMAN BODY ARE LAUGHABLE IN EXACT PROPORTION AS THAT BODY REMINDS US OF A MERE MACHINE. [caps are his]

Anyway he goes on an on with this kind of thing. And it eventually became part of the whole French scene (Bataille, Lacan, Bakhtin, Barthes, etc). Waste, humanity, revolution, you know, it goes pretty deep! And there is an important grain of truth there that sheds light on paths not taken by music, but I left it all out because this is already pedantic enough!