As you can tell by now, this has been an archaeological dig. We broke ground on Melody, which, while ancient, in its current form is the thinnest and most contemporary top layer, marked by the relatively recent trends of commodification, market-driven hyper-innovation and literacy. Ornament was the next layer- ethnic, tribal and reliant on a pre-capitalist commons of culturally-shared signifiers (which turn criminal after the "commons" is repressed). Under that, we found Phrasing, which lasted longer in our memories than the previous two. It is culturally informed, but it transcends that too, stemming from biological experiences of being in a body bound by gravity. Surely, we must be near rock bottom. Is there anything left?

With each new layer we have also noticed that there are fewer and fewer clues. Melody, is found in the library, in the rows of books with rows of dots in them. Ornament took us into the kitchen, where we found teachers who used metaphors of spices and fermentation and constructed menus of options to choose from. Phrasing took us to the basement workshop. A bit more dusty, more doing than talking.

We have one more (sorta) level left, Timbre. Timbre takes us outside the house entirely and puts us in a field. It’s dusk. If people were confused about how to talk about phrasing, at least we knew how to pronounce it!

The Obligatory Timbre Definition Section

Quickly: If you’re new to the concept, the standard explanation of timbre is that it is the difference that you hear between, say, one note played on a piano and the same note played on a violin. Or the difference between me singing a note and Skip James singing the same one. More recent research has focused on the fact that timbre is two things: (1) It’s a quality of tone that can be quantified via various scientific measurements and also, (2) a profoundly elusive element of tone that can sometimes mysteriously move us on a deep emotional level. I'll let other people do the heavy work of definition here (see book below- it does a grand job of summing this up and much more.)

But mostly, it is just ignored. The only discussion of timbre I've ever run across in klezmer comes from discussions of tone (although bc I’m not in violin or clarinet circles this might not be entirely fair). I remember Cookie Segelstein saying "We're tone freaks" about Veretski Pass and Josh Horowitz’s unique accordion obviously shows careful attention to tone. I have no doubt others feel similar about their instruments.

In general, timbre likes to hang out at beginnings (what its doing there we’ll investigate later), as beginner students try to form a single acceptable note on their instrument before graduating on to melodies. In more advanced circles, it is usesd in discussion of "tone color" and is of interest to either composers, who are arranging their orchestral chess pieces, or those musicians who geek out on nice instruments. In the ethnomusicology context, it is sometimes covered by the Russian notion of “intonazia”, a handy matrix of musical grammars that includes tone color, but no one ever seems to ever do more than simply cite that word.

In a model of music that is dominated by melody, timbre will always be the “lesser other,” dismissed as too insignificant or too weird or scientistically reduced to being “simply” harmonics or overtones or something else. But it is possible to hear it another way.

Below Phrasing: Timbre

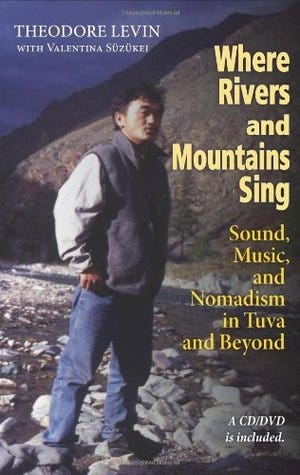

Instead of viewing timbre through the lens of melody, we can let timbre change our mode of listening altogether. In this I rely heavily on the work of Valentina Suzukei, an ethnomusicologist who studied Central Asian pastoralists. Her work I found via Theodore Levin's Where Mountains and Rivers Sing.

Suzukei was trying to understand the music of Tuvan nomads. Being a good ethnomusicologist, she first tried to get the tuning of one of their instruments, the igil. She asked a player to play the strings of the igil separately, so she could get the absolute pitch of each string. The player seemed to not understand. Eventually the musician said "You're a strange girl, go have some tea."

What the musician was trying to demonstrate was that the absolute pitch of the strings was irrelevant to his understanding of the instrument. This in itself is not surprising, but what happened next completely changed how Suzukei heard music:

What was more important, he didn't hear these strings as separate pitches, but as part of one total sound. In other words, discrimination of pitch height, the fundamental building block of melody and of melodic perception, didn't play a significant role in the way this musician perceived the sound of the igil.

If not individual pitches, what mattered to this igil player? Suzukei continues:

For him, pitch was subordinate to timbre... his way of listening represented an entirely different approach to the perception of sound than what you have in cultures where the focus is on melody. You could call this other kind of listening 'timbral listening.’

Timbral Listening

Suzukei says the musicians she studied explained their music "through analogy and metaphor using examples drawn from nature." But in reality, it was weirder than that. They used metaphor and analogy but they also were quite literal- they literally pointed to physical spaces from their actual landscape as being somehow part of the music itself. Their music wasn't a metaphor of those spaces exactly, but seemed intimately and materially connected to them somehow.

How does this work exactly? As Suzukei says, "When you play the igil, there are different layers of sound, and the resulting effect for the listener is what you would call volumetric."

Volumetric? To understand this we have to uncover some of our own deeply held biases about what music is. In our default understanding of music, which Suzukei calls “melodic listening”, we take for granted that music proceeds through time on a 2-dimensional line. It goes from point A to point B, like a line of text. It is hard for us to even imagine that there could ever be an alternative to this, or that this mode of listening would be something we would have to learn as children.

But timbral listening assumes something else. It exists in a three-dimensional world. There is no line going from A to B, instead we are in the "middle" of the sound, and can explore it outwards in all directions. Some practical contemporary examples may help us understand this:

In my first section on melody [note: I haven't put this section on the substack yet], I explained that there comes a time when a musician might become bored with melody. Notes go up, notes go down. Whoop-dee-doo. It all seems kinda flat. I remarked that our musician, a guitarist in this case, might then wistfully remember back to a time when they were a rank beginner and simply strumming a G chord was cause for fascination. That chord was timbral- it didn't go anywhere and yet for some of us, it was an amazingly powerful, however brief, moment.

Another example: In The Music of Strangers, Yo-Yo Ma's documentary about how he got his groove back, a bunch of musicians from all over the world are trying to find their voice as an orchestra. The whole thing is a bit of a narrative conceit, but the musicians do seem authentically stiff in that classical music kind of way. In an early scene, Yo-Yo Ma travels to an indigenous tribe to find The Secret, but, with his melodic sensibility, the interaction ends politely but unsatisfactorily. He and the band then try various other things. The breakthrough finally happens when they least expect it. In a restaurant, the musicians spontaneously start tapping on their glasses. The result isn't melodic, but it isn't even rhythmic either. It's pure noise, or rather timbre, created by some of the most sophisticated musicians on the planet, and to their obvious delight, it goes absolutely nowhere.

Holler!

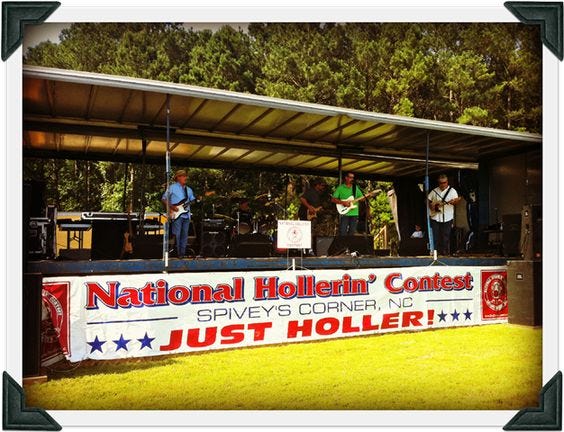

We have homegrown examples of this too. In the rural American South, there is a tradition of hollering, which is found in black and white traditions. People literally just walk out their door, and holler. Bill Monroe specifically cited this tradition as an influence on his music and vocal style. There’s no shortage of theories about the origins of this strange practice (Yodel Ay Hoo: The Secret History of Yodeling does a great job of outlining these theories in a handy chart).

Hollers, like the timbral songs of the Tuvan nomads, go nowhere but also depend on place. No one would ever think to do this indoors (Curiously, in addition to place, time of day seems to be important as this practice is more common during dawn and dusk, reinforcing a notion of crepuscular acoustics that we saw in A Yiddish Guide to Lawn Maintenance.)

Listening

Before we take a look at what this strange form of music means, we should take a moment to notice that, when it comes to timbre, we tend to talk about listening. Why? When we looked at melody, ornament and phrasing, we were in the role of making music. Why have we now become listeners? In the case of the holler, the Tuvan nomads and other pastoral shepherd songs, the active moment of making the music is, at best, only half the process. What happens next is the slow reverberation of the sound through the landscape as it bounces around and descends gently back into silence.

Picture yodels bouncing off hillsides until there is any number of versions of your own voice harmonising in mid-air. Voila, you're recapturing that magical first moment of recorded sound - mountain valley as recording studio”… Plantenga, Bart

Where is the music? Is it in the "hollering" or the echo? Are we making the music or are the mountains making it? What is this primal ruach/voice/big “bang” that divides undifferentiated Chaos into Heaven and Earth, subject and object? And why, at the heart of so many beginnings, do we find timbre at play?