After the Civil War, Southern farmers were in social and economic chaos, and also badly in need of scientific education. The federal government’s Dept of Agriculture sent one of their agents, Oliver Hudson Kelley, down to investigate their plight. He saw that the South was sitting on a tense and sectarian tinderbox, which involved organizations like the Klan, and had a vision that the Government might help somehow and maybe form a group to offer alternatives. His bosses disagreed.

But Kelley wouldn’t quit and, along with some others, he went on to form the Patrons of Husbandry, or the Grange, devoted to the social and cultural uplift of farmers.

Kelley, while in the South, encountered a type of hostility that faced many a Northerner, yet much to his satisfaction he also discovered that being a Mason helped to ease the way for him. The depressed conditions he saw convinced him that if better relations between the sections were restored, they would come through fraternity and not politics. “The people of the North and South,” be believed, “must know each other as members of the same great family, and all sectionalism abolished.” 1

Kelley’s vision of how the Grange would function was also borrowed from his Masonic experiences,

Kelley at this early date was possessed with “the idea of a Secret Society of Agriculturists, as an element to restore kindly feelings among the people.”

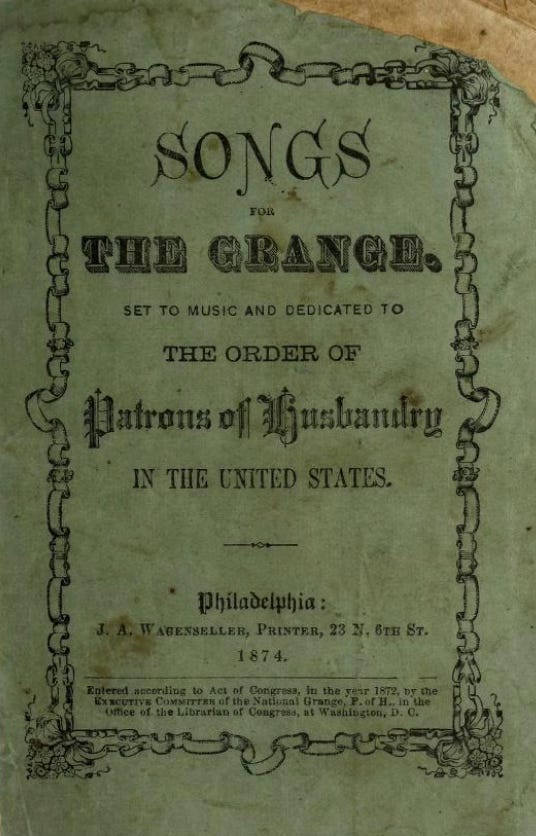

But unlike many Masonic organizations, the not-so-secret Grange left behind a vast treasure of literature and music.

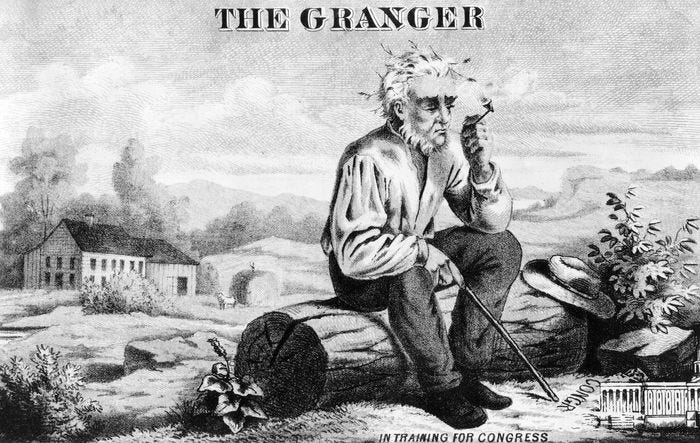

The Trumpet of Reform for the Grange Club 1874

Country music, as it developed in the early 20th century, is usually seen as stemming from both untutored folk and “learned” sacred traditions, but this dichotomy obscures an important third strain of social organizations. Many of these organizations had their own visual, aural (and gustatory) cultures. The Grange, was one of these groups.

Their lyrics are notable for a lack of Christian imagery, so prevalent throughout other rural musical traditions. However, these weren’t dry or boring, as we’ve come to understand secular to mean in this day and age.

Imagine singing that in a big old hall with a bunch of neighbors.

Songs For The Grange. 1874

Neither were the songs flatly materialistic and devoid of the metaphysical. Classical and pagan gods appear regularly side by side with vague references to a more Abrahamic God.

There are references to “God”, and the “Divine Builder” but, in my limited readings (there are a lot of songs), I did not find any direct references to “Christ” or similar imagery that would be familiar from early country or bluegrass gospel.

This worldview was part of the organization itself- one high-ranking position was “The High Priest of Demeter.”

Glad Echoes From the Grange. 1881

You can listen to a modern album of Grange songs, but the influence is conspicuously absent in the development of 20th century country music. Where’s all my bluegrass songs about pagan demigods and sorghum harvests? Why did it’s musical influence wane? Perhaps it was similar to shape-note, which also resisted recording. Or maybe, like the Wobblies, labels were worried that the political aspect would limit the audience or get them in trouble. Or maybe, like the thousands of small town brass bands or mandolin orchestras, it just didn’t make much sense to listen to this music isolated from its social context.

There is at least one old 78 that references and even includes some Grange music. A comedy record that isn’t half-bad.

This ain’t my best researched article but it’s really more about poetry than history. Go ahead and browse those songbooks. Maybe gather some folks and sing them. There’s a ton of nonsense being spewed these days about how secular culture is devoid of values or art or morality or whatever. It seems silly to have to even refute that, but here’s yet another vision of a world that could have been- one of enlightened affection that overcame narrow ethnic identities to foster “kindly fellow feeling” and mutual aid, but was also full of humor, poetry and pie.

Saloutos, Theodore. “The Grange in the South, 1870-1877.” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 19, no. 4, 1953, pp. 473–87.