Why Lament?

"It would appear, then, that virtually all of the terms associated with emotional aspects of the music and, in particular, with ornamentation are expressions of a sad or lamenting quality." (Joel Rubin) 1

Our understanding of klezmer usually begins in Eastern Europe, since this is where the genre (roughly) began. But if you stand back a bit, you can see that klezmer exists as just one in a series of chapters in the long history of "secular"2 Jewish music. The cultural rupture that happened during the Eastern European phase of Jewish culture makes this history even easier to ignore.

The lamenting quality of klezmer is often discussed, even by learned folks in the klezmer scene, either in terms of mourning for the destruction of the second temple or the old world desire to make a bride cry because of the painful transition that the wedding represents in her young life. But these lamenting traditions existed well before the destruction of the second temple and have pagan, non-Judaic roots as well (as Joel Rubin suggested). In fact, the lament as it existed prior to the destruction of the second temple is perhaps more relevant to klezmer.

Why do I see a connection between klezmer and the earlier, lamenting traditions? Specifically, we find shared practices and attitudes towards music, dance, gesture, and improvisation. As we’ll see in the next post, both groups share similar social roles. We will also find some important differences, such as attitudes towards words, gender and death, which will shed important light on how this strain of culture evolved through history. But most importantly, at the center of the connection between the lament and klezmer, is the mission shared by both, to make people feel things. 3

As obvious as this feeling-centered musical mission may seem to us modern folks, this is something that distinguishes klezmer from many other "folk" or dance musics, especially those European-derived strains found in America. Our current understanding of klezmer as the Jewish equivalent of these other folk musics has obscured the affective (emotional) role it played and reduced the genre to a bunch of notes that just happen to be ornamented in a historical way that is now locked in time.

An exploration of the lament and the techniques it uses to make people feel things will help to explain the story that I think klezmer is trying to tell and how it tells it. Understanding how klezmer musicians and others from the past heard the lament can also help us understand possible next steps in that larger historical struggle between normative Judaism and its repressed margins.

In The Wilderness

God said to Abraham "Kill me a son..."

You probably know the story of Abraham and Isaac and the aborted sacrifice, but do you know the other biblical story involving familial human sacrifice that came about generations later and had a... less happy ending? Yup, it features a woman.

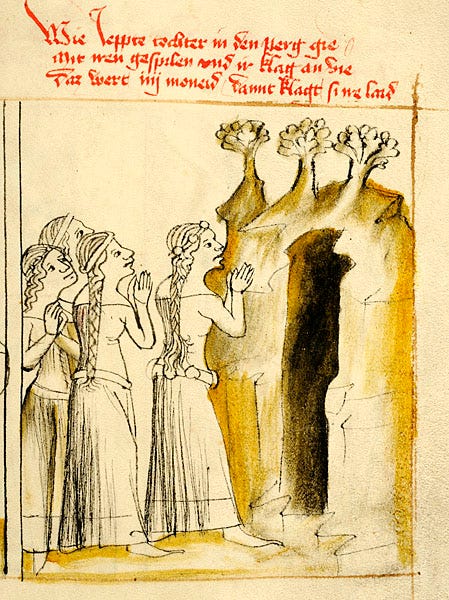

The beginning of the lament in Jewish tradition is traced back to Jephthah and his daughter. Long story short- Before he goes into battle he promises God that, if granted victory, he'll sacrifice the first person he meets on his return. Of course, he is victorious, and of course, the first to greet him? His daughter. This time there is no angel holding back the blade, and the deed is done. But before that, her wish to "weep for my virginity" in the hills for two months is granted. And so she does, telling the rocks about how she'll never get to be married and have kids.

Two things about this story stand out.

One, Jewish women had a much larger musical role in Biblical times. They not only lamented, but celebrated and even prophesized.

This dialectic between sorrow and joy4, two emotional opposites affording opportunities for outbursts of extreme sentimentality, can be seen in the victorious exultation of the women following David's triumph over Goliath: Bar-Ilan.

Jephthah's daughter was first to meet Jephthah because she was celebrating his victory, "dancing and playing tambourines." The transformation of this joyful role into one of great sadness mirrors the evolution of women's musical roles in Judaism. The celebratory cults would be the first to go and women would be left with lamenting as their main opportunity for creative agency and leadership.

The story also contains a mystery- why did the daughter go to the mountains to lament? What good does it do to wail to a rock? As we saw in our earlier investigation of timbre, this "singing to the landscape" has important musical, anthropological and psycho-spiritual implications, but now mourning adds another dimension. Mourning would seem to involve a temporary ostracization from the community. We see this idea reinforced in the various otherwise anti-social behaviors that are considered customary during the time of mourning. We are, for a while, in the wilderness. This will be explored later.

A Guide To Keening in the Biblical Era

The Jephthah story is fascinating, but probably not a historically accurate depiction of the origin of keening. In truth, of course, "keening" (I'm using the popular Irish word used for this practice of professional mourning) was widespread in the Ancient Mediterranean and beyond. It was not restricted to the ancient Israelites (there are multiple examples from some of the earliest cultures in the region) nor was it entirely restricted to women.5

If you're like me, you may have done a double-take at the phrase, "professional mourner." Huh? But there were a class of folks, predominantly women, who were specifically called upon to perform this function. Why and what was this function exactly?

Before getting into the meat and potatoes we have to unravel some threads. I use the word "Lament" in the title because that is the term most widely used in this field, but its a little confusing because professional mourners vocalized several genres, one of which included a song form called the lament, but there was also wailing and dirge singing. These distinctions shouldn’t be considered legalistic, but we know there were attempts to distinguish minor differences amongst them because of later regulations:

What is a lamentation? When all sing together. And a wailing? When one begins by herself and all respond after her (Mishnah Mo'ed Katan 3:9 cited in keening women)

Singing and Music

As we saw in the quote above, a key component of the vocal art featured some form of antiphony (call and response) group singing. It is interesting to note that, in the case of antiphony, women would have been in leading roles over mixed-gendered groups, and leading those groups using their own creative compositions.

In contrast to antiphony, there were also times when "all sing together," although I haven't seen much documentation of that. On the other end of the spectrum, there was also a form of mourning in which all would chant more or less hetereophonically amid wailing and crying. Curiously, this last category was seen as the most subdued variety, perhaps because it required the least amount of cohesive group attention.

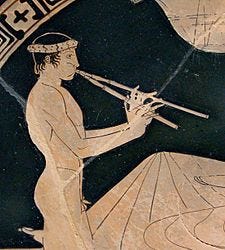

Musically, there is evidence of percussion (often body, small drums, clapping or foot stomping). There were, no doubt, lots of regional and historical variations, and that is important because it reminds us that this practice was originally based in custom, not law. One later reference mentions that a minimum of two flutes were required.

Rabbi Yehuda says, "Even a pauper in Israel shall not employ less than two flutes (halilin) and a wailing woman"

Why two? It may have been that the number of musicians denoted status and two was seen as a dignified minimum. But when it comes to flutes, keep in mind that this ancient flute was not the sweet-sounding modern flute, but something much more shrill. Two of them would have provided a wild ecstatic dissonance. Sendrey says this term is erronously translated as flute and “was akin to the full fledged Greek aulos” belonging to the shawm family. We've explored this flute magic before.

The description of Jewish pipe blowing would not be complete without mentioning its power to induce a state of trance. The apocryphal acts of the Apostles relates that one day a Jewess played the pipes behind St. Thomas for an hour before he got into an ecstasy and none could understand the words he then spoke except the piper. (from Curt Sachs, mentioned in this post)

All of these attributes in this section are consistent with lamenting traditions in Ancient Greek culture (see Alexiou), who also notes the shrill piped accompaniment.

Dancing

Was there dancing involved in mourning? Cia Sautter seems to think there was, but to do so she seems to be conflating "journey to the underworld" fertility type dances, (see limping dance) with more personal funereal customs. That might be a bit of a reach. I'm not sure why, but she fails to cite Bar-Ilan, who provides more convincing evidence hidden in a footnote:

In the Jewish tradition, dances of mourning are never mentioned explicitly. However, in the Peshita, the Syriac translation of the Bible, the verb 1-El-O , to mourn, is translated "dance." For example, when Abraham mourns Sara (the sole biblical incidence of mourning over a woman), Gen. 23:2 "Abraham proceeded to mourn for Sarah and to bewail her," (translated into Aramaic as "to dance for Sarah and to bewail her"; and Gen 50:10: "they held there a very great and solemn lamentation," translated in the Aramaic as "they danced there a great dance." That is, mourning was identified with dancing, like the tradition in the book of Judith that connects mourning with clapping hands and stamping feet.

Alexiou, studying the ancient Greek traditions, does see clear evidence of dance:

The archaeological and literary evidence, taken together, makes it clear that lamentation involved movement as well as wailing and singing. Since each movement was accompanied by the shrill music of the aulos (reed-pipe), the scene must have resembled a dance, sometimes slow and solemn, sometimes wild and ecstatic.

Sendrey also believes there was dancing although he notes that, “there is no mention, in the Old Testament, of dances at funerals.” His evidence is that (1) everyone was doing it in the Mediterranean basin, (2) the instruments used at the funeral were also used in dances, (3) lots of funeral customs we know existed didn’t make it into the Bible because of their pagan origins and that there was (4) a kind of group foot stomping that was likely a dance. His last piece of evidence is that (5) funeral dances are documented shortly after the Biblical era, in Talmudic and post-Talmudic times, and that these dances represent a continuation of a “primeval custom which, in a transmuted form, has survived to our own days.”

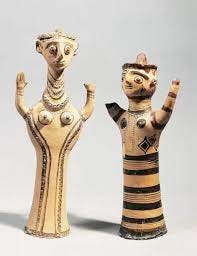

Gesturing

Gestures, however, were very clearly an important part of mourning. Bar-Ilan writes:

The parallelism between beating the breast and chanting dirges indicates that it is part of the same action: the women would beat their breasts and lament like the ancient keening women in Isaiah 32:12: "Lament upon the breasts." That is, women would beat the breast to express grief when keening.

In all-too-brief footnote, she also mentions something that sounds oddly like klezmer dancing:

We learn by the way of another custom, of spreading the arms while praising the deceased (while walking, in a kind of dance.)

Alexiou takes up this discussion of arm gestures in the Greek context:

The raising of the arms which can be traced back to Mycenean painted lárnakes (coffins) and to the earliest vases of the Diplylon period, is perhaps the most frequent and the most ancient, although its precise origins and significance are unknown. (pg 6) along with "stretching out" of the hand and putting a hand on the breast of another. 6

Feeling

Why hire a professional mourner? I've not been able to find the specific reason in the Ancient Jewish context, but other cultures have provided them. The general idea is that without being properly mourned, the deceased is in danger of not making the journey and/or getting mad at the living for screwing this up. But in order for it to work, the loved ones have to really get into it, hence the mourner's job is to get the tears flowing. Anyone who has lost a loved one will understand this, as it is still the practice in mourning traditions to heighten what is already a very sad time, in order to help loved ones get over their denial, accept the situation, and let the deceased go.

There may also be weird anthropological reasons. In the very olden times, having people make noise around a corpse was important to keep predators away. Ted Gioia has suggested the theory that keeping animals away from recent kills might be amongst the earliest sources of prehistoric noise-music. I think Sendrey says something similar somewhere. In later times, when predators weren't as much of a practical problem, the tradition may have been re-imagined in the context of bad spirits.

Later rabbinic interpretations retrofit keening into Jewish religious law, but the practice is most likely rooted in pagan or pre-Judaic beliefs, something the rabbis were ultimately all too aware of.

Creative Agency

There is evidence that laments, dirges, and wailing were unique and creative works and prized as such. Again, the wailers were called "wise women" and not just "swell singers." In addition, this was seen as enough of an artform that it was something that should be taught from mother to daughter.

The singers of joyful hymns and the keeners of dirges, demonstrate the independence of women acting without husband or family, gathering to sing and chant on special occasions of triumph or mourning. (Bar-Ilan)

This type of literary composition was aided by various techniques and tropes, but they will have to wait for the concluding post since I’ll be bundling them up with other techniques from other times and places.

One more note about the "wise women." They are sometimes referred to as "prophetesses.” This is not hard to understand- lamenting a person required improvising on that person's struggles and life story. Apply the same process to a Nation or even a God and, boom, you got prophecy. See Bar-Ilan for a more analysis of the “wise women.” It may be that these wise women are the last in a strain of Mediterranean female-dominated spirituality that overlapped with early Judaism. Obviously a topic for another time.

And keening was originally just one of the services on offer by the wise women:

It may be concluded that the singers of triumphal hymns and elegies were also the wise women and prophetesses. In times of national disaster they would keen, and in times of national triumph they sang songs of bravery and praise. On a daily basis they would dispense their wisdom to people coming to consult them, or serve as professional mourners at local funeral processions. (Bar-Ilan)

Power

Imagine you’re in a circle of people. In the center is a dead body. People are crying and murmuring amongst themselves. All of the sudden, one of the women in the circle changes her posture and sits up slightly. People fall silent. Her arms raise. A cry emerges. Is it possible that sound is coming from her body? You are defenseless as the tears immediately come forth.

We can safely say the old time keening scenes must have been quite powerful. Why? Because they were meant to be. The wise women were powerful women, which was expressed in their songs as well as their social role as leaders in these scenarios. And yet, that power would end. The Wise Women, and their traditions, would end up as “the lesser other” to their male priestly counterparts. But, as is typical with this strain of culture, it is never completely defeated, and we will meet their songs again in the next post in this series.

Next, The End of Biblical Keening?

Rubin’s footnote mentions, as I repeat in the 2nd para, that klezmer’s sad quality may express the usual suspects, (1) the religious mourning for the fall of the temple, and (2) the seriousness of the marriage transition, but also that “these aspects, as well as their possible roots in Pre-Judaic times, have been amplified in Ottens Rubin Klezmer-Musik.” I’d love to know more about that amplification in case anyone has a copy.

Klezmer is sometimes described as “secular” Jewish music, but this term is obviously problematic. I’m referring to music that forms a countertradition to, or is outside of, the dominant priestly culture. In the case of the lament, you could make a case that for a good chunk of its history, it was neither secular nor Jewish!

“..Summon the dirge-singers, let them come; Send for the skilled women, let them come. Let them quickly start a wailing for us, that our eyes may run with tears, our

pupils flow with water.” or: “Tarras recalled accompanying his father on the clarinet at kale bazetsn ceremonies in the Ukraine '“I used to play crying music… to help out and make the women cry.’” cited in Joel Rubin NY klezmer.

Ed Sanders calls this the “oi-joy spectrum.”

Or even mortals! See Sumeria, where Ningal, a goddess, lamented. Also, “At the heart of the ancient Babylonian city laments, the poetics of which may have been incorporated into the Biblical Book of Lamentations, were weeping Gods and especially Goddesses, who lamented their destroyed temples and cities.” - Lament in Jewish Thought Galit Haskem Rokem) emphasis mine.

"Putting the hand on the breast of another" is similar to a move in klezmer dance where the hand, instead of being stretched out to the side, reaches briefly directly outwards towards the other person, and twists ever so slightly to the center of the body as if trying to overcome distance.