"Run Lost John to the top of the hill;

Ain't caught Lost John and he never will,"

We saw in the first post how “crooked music” works to increase participation amongst musicians and audiences. These little moments of musical grid-breaking were called "participatory discrepancies" by ethnomusicologist Charles Keil, who says that music, in order to mean something, needs to be “out of time” and “out of tune.” A little later, in the same essay, he makes a weird observation:

Certainly the textural or timbrel participatory discrepancies tend to be wilder and crazier the further back and further out one listens. Or is it the further up? I'm thinking of all the pitch discrepancies in mountain musics all over the world: Tibet, Appalachia, Epirus, the Tatras.

Keil intuitively connects geography to participatory discrepancies and it's an interesting move. Whether it's the "half barbaric twang" of the banjo, the insanely gritty fiddle of the Polish countryside or the mind-bending worlds cracked open by Epirotic clarinetists, these places, though geographically very distant, share a sonic preference for wild dissonances.

Anthropologically, this could be a case of core vs. periphery. Peripheries tend to be a little more ragged, as might be expected. But if you go even further out from the periphery, you reach another place… Zomia. Zomia is, roughly speaking, just a fancy word for any place that is a pain in the ass to get to. Why would anyone go there? To get away from the authorities, like a government and its military conscriptors or tax collectors. In essence, zomias are places where people go to escape.

James C. Scott, who popularized the idea of the Zomia in his book, The Art of Not Being Governed, demonstrates how the cultural practices of the people who live there make sense when seen in the context of their political preferences. At first it might look like peripherial raggedness due to cultural decay. But if you look closer, their practices make sense as an intentional practice.

For instance, many Zomian people have a story of having had literacy but then losing it. Is this just ignorance? Well, losing literacy is useful to people for whom the written word was mostly a source of oppression, in the form of tax collecting and legalized slavery. Therefore, their illiteracy was a sort of semi-conscious tool to maintain the sort of society they want and avoid the hell they came from. [Pierre Clastres deserves credit for developing the idea that societies use cultural practice as a way to avoid the tendency to form authorities in his book, Society Against the State.]

Keil’s original focus on places that are “further back and further out” is a perfect definition of Zomia, but he doesn’t make the connection to its cultural and political implications. He gets distracted by altitude: “further up” and the specific issue of pitch (which may have something to do with echo, to be investigated later.) But let’s focus: Is there a musical connection between place and participation?

Tunes from Limbo

Let's take a look at two examples of songs that found their way to me in the suburbs of Philadelphia: the Jewish doina and the American Lost John. Both are very much related to Zomia (though importantly, not directly Zomian) and both feature heavy doses of “participatory discrepancies.” I believe they make sense when seen in their relation to zomia.

1) They aren’t really songs: Neither the doina or Lost John are quite “songs” or “tunes” in the sense we think of them today. Curt Sachs makes a distinction between western songs, fixed forms that are supposed to be repeated more or less identically each time, and “Oriental” songs, which are vague melodic outlines that are supposed to be reimagined and improvised on with each performance. The doina and Lost John fall into the latter category.

Lost John, often lumped into the strange category of “pre-blues,” is basically a simple vamp or riff repeated indefinitely with plenty of space for improvisations. Like the doina, it is expected to sound differently every time, and although its been recorded countless times, very few versions are identical.

2) They aren’t written. That “oriental” approach is why it doesn't make much sense to write them down. To play them out of a book would defeat the purpose. Lost John and the doina conjure a sense of freedom and possibility embodied in their improvisational aspects. This seems to be a key component of the oriental mode; hat, because the intent is to be expressive, there is less emphasis on a written score. (This doesn’t mean there aren’t rules- this isn’t free jazz- there are a ton of rules.)

3) The melody is not the point. The doina and Lost John are complex in the sense that a lot is going on, but this is often trickery! The Lost John vamp is rhythmically hypnotic and the doina is often full of bewildering but not very complex arpeggios.

While the melody is basic, the ornamentation, both rhythmic and melodic, is fiercely virtuosic. This is where Keil’s discrepancies happen. It's as if these songs represent music as it has evolved in a parallel universe, where participation was the goal and where most of our assumptions about what a “song” is are turned upside down.

4) Finally, and strangely, both have roots in pastoral “sound mimesis.” This means they recreate a place or event sonically. The Lost John riff is identical to the Fox Chase1, which is a narrative depiction of said chase in sound (the text of Lost John is a human chase, as we’ll see later.) The doina is a classic pastoral shepherd’s song, which is played to, with, and in some cultures even represents, the landscape that it is played in. This will be the subject of our post on timbre and timbral listening. Some recordings of them feature purely timbral elements like cowbells and sheep braying to make the point.

That covers the important formal similarities between the two songs. But what about the content of the songs?

Who was Lost John?

A negro criminal who ran away whenever he wanted to and was caught only when he wished to be. The song describes a prison break. A convict runs through the woods with guards shooting at him. He reaches the shelter of the woods, and someone goes for the dog-man, master of a pack of bloodhounds. Then for hours the chase goes on, the man using every trick he knows to cover his trail.... (Alan Lomax, 1960)

Lomax connects Lost John to the archetype of John the Trickster Slave. The "tricks" he uses allows the enslaved person to succeed no matter what the odds. He can "hit a straight lick with a crooked stick" as the saying goes2, and through his superiority creates a topsy-turvy world where everything is opposite and the enslaved becomes free. In another absolutely brilliant verse, Lost John “has a shoe with the heel in the front, and the toe behind, you can never know where Lost John was gwine [sic].”

This dynamic mirrors and fractalizes into the music itself, which, in its deviance from the dominant “western” songforms, uses low-down low-class rhythmic tricks to beguile the listener, seducing them into participation. Just as Lost John the person is literally hiding, the song too is careful not reveal too much about its true radical origins. As Lomax says, "The song too, is a chase..."

The Wordless Bandit Ballad

In the context of the doina, we have, as usual, a deficit of sources. Doinas are everywhere in Romanian and Eastern European culture, but the Jewish adoption of the form, and what it meant to them exactly, is shrouded in a bit of mystery. However we have one very interesting and important example that found its way onto a klezmer anthology edited by the great Martin Schwartz, The beautiful and mysterious Kleftico Vlachiko by the Orchestra Goldberg:

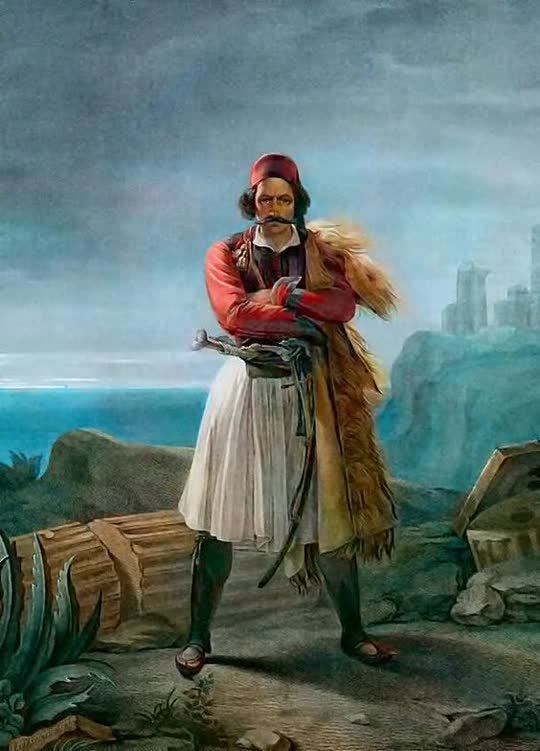

The title of the present selection, "Kleftico Vlachiko," is made up of two Greek words, the adjective vlachiko, in this context amounting to " Romanian (Moldavo-Wallachian)," and the noun kleftiko, referring to a type of Greek regional non-rhythmic heroic ballad, named after kleftes or brigands, mountain warriors who took part in the Greek revolution against the Turks which ended in 1821" - Martin Schwartz, Liner Notes (folkways)

Like Lost John, the klephts were so-called primitive rebels who chose the mountains as their zomian refuge. Klephts under Ottoman rule were generally men who were “fleeing vendettas or taxes debts and reprisals from Ottoman officials.” They raided travelers and isolated settlements and lived in the rugged mountains and back country." [There is some confusion in the title about the Romanian vs. Greek thing here. Zev Feldman refers to the song not as Greek but as a "Romanian Haiduc/Bandit Ballad." The Romanian Haiducs were very similar to Greek Klephti, also living in hard to reach spots and fighting the Ottomans. Perhaps Zev does this because the tune is, as Schwartz notes, Romanian, but the label uses the Greek term for marketing purposes? Consider this example of an anti-authoritarian “haidouks” song and its similarity to the Moskowitz doina.]

Similar roles of the fugitive in Rebetika and Flamenco are briefly considered in a footnote in this post.

Jewish Doina and the Pastoral

Scholarship on doinas usually contextualize them within the forms of the Ottoman taksim and the Romanian Doina Oltului. Both are semi-improvisational and have “flowing” meters. These are obvious sources for the Jewish doina, just based on formal considerations alone. But both have cultural contexts specific to Ottoman and Romanian culture. What did the doina mean to the Jews?

Klezmer itself has an under-appreciated “pastukhl” or pastoral aspect, which was more obvious to its original audience but has been mostly lost to modern listeners. Joshua Horowitz has argued convincingly that the doina was understood by audiences as a pastoral allegory of King David and recovery of the lost sheep. This is undeniable. But is the music nothing more than allegory? Do any of the Zomian overtones creep in?

Suggestions to this effect are usually met with assertions that Jews weren’t bandits, in fact were quite wary of anyone so cossack-like, and that these songs weren’t rural in the Jewish context, but specifically developed in urban spaces like cafes.

But I don’t think these songs are zomian- I think they refer to it. Lost John isn’t sung by Lost John, it’s sung by folks in bondage looking to the story for hope. Perhaps doinas are performed for polite audiences in cafes in the same way. For instance, In America, the role of the pastoral was filled by the cowboy and some of the earliest folklore was targeted on them. But cowboy songs on 78s were not authentic expressions of actual cowboys. They were self-conscious artificial constructions meant for shitkicking farmers who idealized the cowboys’ free way of life.

This demonstrates a common phenomenon found all over culture. People in one class/strain projects onto another, usually older, class/strain. What do they find there? Freedom, meaning. It’s why I, a computer worker (information), like to garden in my free time (agriculture), but my farmer brother-in-law (agriculture) prefers to hunt (hunter/gatherer).

I’m not arguing that Jews in the old country saw themselves as hip rebels whenever they heard a doina, but I am noticing that a good chunk of the music that means something to folks all over the world resonates along these political and social lines in ways that aren’t always clear.

Out of Time, Out of Tune… Out Of View

Historian Eric Hobsawm wrote a book about these so-called “primitive” rebels. In it he notes that “the bandit is not only a man, but a symbol” and the symbol has an appeal much wider than the historical one. He also notices that it is a strange aspect of these folks that, besides Robin Hood, our ability to retain memories about the insurrectionary moments is oddly very short. Like a dream, we grasp the feeling without being able to hold on to facts.

Why is this? He’s not sure. These bandits emerged, he says, in a very specific time and place: peasant societies during early capitalism, and he believes that we moderns have a very hard time inhabiting that mental space. There is something always “lost” and just out of view.

But this also might be because this culture likes to stay out of view.

We saw this with Lost John and the deliberate ambiguity found in it’s performance. But this comes at a cost. Lost John and the doina have lost favor over time. Our ability to play them, or more accurately, to hear them is fading.

Lost John is now seen as a curiosity, an uncategorizable holdover from a distant past. It's one notch up from a holler, associated with the limited and low-class harmonica, and often found in the company of other similar “non-songs,” like train imitations and fox chases. In white musical circles, it was first kept on for its humorous content and then later cleaned up, lyrically and melodically, and “fixed”- turned into a more conventional “western” song.

But this co-optation was a little too easy. I doubt most white musicians today even know what it means. For instance, the song is often titled and sung as “Long John.” Subtly, the meaning of the song is ever so gently obscured. Consider the dogs chasing the escaped slave in this lyric:

Had an old dog and his name was Will,

Run Lost John to the top of the hill;

Ain't caught Lost John and he never will.

Who owns the dog? The singer? Why is John running? Whose side are we on? These things are, very consciously, not spelled out in the versions collected by white folks, but would be plain as day to African Americans at the time. The goal of oppressed people is to, according to James Scott, "stay out of the archive." The songs’ meanings and forms prefer to smuggle themselves out via more conventional forms, making themselves obvious only to those who know how to listen. And so far, they’ve succeeded.

The elder Weintraub performed mainly his own compositions and improvisations. One of these, Der Hirshn-yagd (The Stag Hunt), based on the lament of David for Jonathan, the stag or gazelle of Israel, developed into an allegory of Israel hunted by the nations. According to Stutchewsky, 'Shmuel and his son immersed themselves in it and expressed the joy and sorrow of Israel, the terror of exile, the mercy of God, the love of torah, the yearning for the return and the depths of prayer and supplications of the soul. Although Stutchewsky (probably quoting his local informant) states that 'its origin was a composition of one of the great composers of the nations (i.e. non-Jewish)', it seems more likelty that the piece was based on a version of the programmatic stag hunt or foxhunt compositions known from European folklore, e.g., the Irish foxhunt pieces for Uillean pipes. Apparently, the Weintraubs would perform this piece in the synagogue at the close of the sabbath.

POlin- page 32 Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Volume 16

Focusing on Jewish Popular Culture and Its Afterlife

Writing from August 2024, James C. Scott has recently died. In his last posthumously published article, he writes: “Thanks to casting a wide net, I found dozens and dozens of insights that came from folklore, novels, and other sources. One of my favorite gems is a Jamaican proverb: “Hit a straight lick with a crooked stick.” My conception of hidden, disguised, and openly declared transcripts is wholly derived from the efforts to understand a full culture of subordinate peoples.”