Alright, this post is a bit wild. Here's the four parts:

1. Gesture reinforces Phrasing.

2. Gesture, being embodied, reveals new aspects of phrasing.

3. Practical challenges of incorporating #2 in the contemporary world.

4. Afterword: Historical considerations from the deeper past.

Skip ahead as you wish.

PART I: GESTURE REINFORCES PHRASING

I'm in Raleigh North Carolina and have just finished a little Hanukkah klezmer show. Two older women in the audience approach to thank me. I forget what we were talking about, but at some point one of them was talking about “the world” and she moved her hands as if to grab an imaginary planet. And time stopped.

It was so beautiful, so delicate, I was instantly hypnotized. She didn't grab the imaginary world like I would, as if it was some kind of dumb invisible bowling ball. She caressed it. It was more like a baby's head than a geometric abstraction. The gesture was deeply embodied, sensual even, but also, the epitome of restraint. At the same time, it conjured up similar movements that I had seen all my life but never noticed.

It said more about klezmer phrasing than I had just said in my entire concert.

The connection between gesture and phrasing was actually made at the very beginning of this discussion on phrasing, "He sang me a phrase [signs]." When it comes to melody, we have notation, ornament has its metaphors, but phrasing seems to be found in the hands and arms.

Zev Feldman (and others) have been researching and teaching the connections between gestures, especially in dance, and music for a while. A short essay he wrote about it shows similarities to those aspects of phrasing (asymmetry, variation, agogic/rubato expressivity, and restraint) that I found interesting in the music.

Klezmer Phrasing is Not Jewish Phrasing

But before we dive into those similarities, Feldman confirms something else we saw in the last post.

In 1986, Felix Febich (1918-2014)—a noted Yiddish professional dancer of Polish Hasidic origin—summed it up well. After viewing a video at a conference on "Jewish Dance”, shot among Lubavitch Hasidim in Brooklyn, he reacted: "These are not Hasidim. These are Cossacks!” That is to say, the new American-born Hasidic community emphasized male group solidarity at the expense of individual expressivity, let alone "transcendance."

This lack of expressivity was the same thing that bored Marty Levitt about the hasidic music culture that we saw in an earlier post, "[The hasidic dances] were boring and (the audience) didn't seem to appreciate any of our musicianship." I add this just to remind ourselves that klezmer phrasing is not synonymous with some kind of overall Ashkenazic phrasing but is its own thing, has its own history and represents its own cultural values (and even within the genre ,there is not agreement, see Brandwein vs. Tarras).

We've got a lot to get to, so I'm just going to bring up the categories and let Zev talk for himself. [these quotes are taken from an online article and his chapter on Dance in his book. The article seems to be an earlier version of the chapter on dance for the book.]

Asymmetry:

Symmetrical movements of the arms and hands could be tolerated only for short periods... As in the prayer davenen, there was no need to move with total uniformity; on the contrary, what was considered Jewish was a continual interaction of each individual with the collectivity. Too much uniformity was considered definitely un-Jewish.

Music performed for dances in the core Jewish repertoire should use somewhat uneven, non-repetitive phrasing that explicitly fosters an expressive, creative rhythm environment...

Jewish dance music and Jewish dance co-existed with a certain degree of dissonance, because the closed, largely symmetrical structure of the music was not reflected in the dance.

Variation:

Even the average Jewish dancer, while dancing in a line or circle, was able to express him or herself through continual movements of the shoulders, and subtle variations in steps.

A skillful klezmer would know how to vary the phrasing and ornamentation of a given melody to provide fresh opportunities for response from dancers.

Independence:

The gestural expression within such tunes usually was independent of the motor rhythm of the musical piece and the dance.

Jewish inflected accompaniment for a dance melody would, in addition to indicating the essential rhythm, respond subtly but widely across the arc of the melody to both inflect and emphasize small changes in mood, modality and phrasing.

Connected with Rubato/Agogic:

Jewish solo dance de-emphasized the motor rhythm and concentrated on gesture. Such gestures relate closely to melody, rather than to rhythm alone... One of the techniques of Jewish dance was to simultaneously move the hands and upper body to a different rhythm from the lower body.

An experienced group of [dance] accompanists would provide rhythmic texture... this could be expressed through choices about which beats to emphasize, whether or not to create rhythmic flexibility between beats, and whether to add additional subdivisions between primary beats.

Restraint:

Boris Aronson (originally from Kiev), speaking about his costume for “Hasidic Dance”, wrote:

“It is built on the static, on the quiet moments of pacification of the soul, which is the complete opposite of Slavic dance; the dancing Slav transcends himself, becomes excessively dynamic, jumps and spins very fast;….the Jew however, dances slowly, calmly, deep within himself…”

Aronson’s statement is in agreement with the ultimate goal of Jewish dancing as expressed by the Polish klezmer and dancer Ben Bazyler (1922-1990): Men tantst az Got zol es zeyen; „one dances as though God would see it.”

Seeing my confusion, Tarras got up and began to dance the tune for me... the whole performance had a restrained, but vaguely comic effect...[I realized].. our performance was too earnest and aggressive to fit this kind of dance.

As I said in the last post, these attributes are by no means complete. They aren't meant to 100% explain klezmer, which is composed of many strands and styles, nor are they unique to Jewish music. I have found them useful as ideas because, having named them, one can begin to hear them a bit more. But more importantly, these four ideas have implications beyond just being musical ideas. They serve social purposes.

PART II: GESTURE REVEALS A SOCIAL ASPECT OF PHRASING

Gesturing Towards Others

Musicians love to steal any and all musical ideas from a safe distance. But ask an American male to dance with his hands slowly floating above his shoulders and it's a different story! It's awkward as hell! It violates our ideas of masculinity and leaves us feeling exposed and vulnerable. We feel a little phony too. This awkwardness can be useful because it demonstrates that things like asymmetry, restraint, etc aren't just formal attributes found solely in the grooves of a 78, but existed in social situations which gave them meaning.

In order to fully participate both in religious and intellectual life a Jew had to gesture.

Gestures enabled participation with others. Consider Naftule’s, um, gestures in the context of a performance we saw in the last post:

[Naftule] started coming around to each table playing...He would come near them and play and the clarinet would go almost down into their breasts.

Brandwein is an extreme example. Here we can almost taste the phrasing. Brandwein's erotic preferences may (or may not) be an exception, but many rituals featuring klezmer were explicitly arranged around making people feel things.

The kale bazetsn ceremony marks the bridal couple's passage to married life, and features improvised but formulaic rhymed verses sung by the badkhn or marshalik ... The musician knew the moods at that time, and could express the listeners' feelings and make them cry..

This quote reveals a remarkable idea- the musicians were (1) intentionally expressive and (2), foregrounding not their own feelings, but those of the main characters in the drama. #1 seems obvious perhaps, but we should remember it is not a goal of all music traditions (Old Time music doesn't really speak in these terms, for example). Even a genre as expressive as pre-war blues doesn't quite explicitly prioritize the audience's emotional state (#2) in the same way. But how does this particular expressivity work?

Theater

Jane Cowan's amazingly exhaustive examination of dance in a Northern Greece town takes a look at how music and dance interact in a Greek community. Greek culture isn't Jewish culture (see afterword), but if you've read that book and Zev's chapter on Dance, you will notice some similarities, especially around the role of the audience and expressivity. You might also be in awe of how every teeny aspect of the dance ritual was encoded and structured with meaning for that community. At times it feels less like a dance, and more like a play, where everyone, musician and audience, knows their lines and cues.

As with the Greeks, there are Jewish dances, like the broyges tanz and others, where explicit dramas of resentment and reconciliation are reenacted. There are other songs where looser narrative motifs are found. For instance, many tunes have two minor parts followed by a major part. This so-called pastoral motif is a story of the lost sheep that is found after being lost. This narrative is also found in doinas (Josh Horowitz). It's become a cliche for musicians of all genres to use "storytelling" to enhance their playing, but in these cases, it was an obvious and appropriate part of an expressive goal.. "[Brandwein] acted actually... I would say he became part of the song. He was telling a story." Epstein on Brandwein (Rubin)

On Pre-tending

One further aspect of this theatricality should be stated, which is made clear in Cowan's book. As with the professional lamenter, there is a "fake it to you make it" quality to this, where the expressive gestures come before the emotional payoff, as opposed to being spontaneous expressions of them. In a few of Cowan’s anecdotes, being seen making the gesture is just as important as actually feeling the feeling. For various reasons, including Southern Protestantism (see faith vs works), this is sometimes an awkward sell to Americans.

Even in places where specific narratives don’t apply, Feldman poses a series of even looser narrative binaries like “young/old” or “free/restricted” which form little aesthetic centers of gravity around which performances orbited.

As musicians, we might be able to recover some of these narrative styles, but even if we do, most of it will be entirely lost on modern audiences. Even if we educate them during performances, they won't be able to uphold their part, which was not just to understand the story, but to be the main actors actively reenacting it. That ritualistic sense of participation and the elaborate codes of behavior that held it together may have just been too delicate to survive. Instead of becoming pregnant little archetype mythemes, they’ll just be really really boring stories. I'd love to be proven wrong.

PART III: PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Could we make a bride cry today? No, not in the same way. Times change, and thankfully, 13 year olds are (almost) no longer being ripped from their families and handed to strangers. The distance between me and that world is much wider than it seems, and the more I learn, the wider it gets. How can someone like me, who was more interested in ninja turtles than marriage at 13, relate to these traditions?

Seeing

One of the most touching moments in my musical life was seeing a krenzel, or crowning ceremony, where a mother who has just married off the last of her children is honored and "crowned." The music, during that event, instantly just made sense, and no story was required besides the one in front of your eyes.

These moments of recognition when the dance members explicitly see each other and are seen by them, are one of the fundamental themes of Cowan's study. It is also something completely absent in modern popular and traditional music. This phenomenon is similar to the Jewish practice of shining (shaynen), where someone momentarily grabs the spotlight (obviously not restricted to Jewish music). But in Cowan's study, as with the krenzel, it takes on a deeper, more subtle feeling. Consider this moment, a Greek solo dance, where the dancers' focus was intensely introspective:

However much the dancer dances for himself he only does so in a public setting. This stylized choreographic articulation of the lone self is always posed to a watching audience, and it is those youthful male peers who witness and, by their supporting gestures, validate his performance. (Cowan)

, "...[S]eeing others, and being seen, is a way Sohoians show their membership in the community." (Cowan). This is not just shining. This is not hippy dippy new age stuff either. Being seen and seeing can get complicated quickly. The naked desire for status is not always pretty or aesthetically pleasing (see my Bar Mitzvah party). Cowan describes the dance as a place of "sociability but also competition, display but also exposure."

The risky business of seeing/being seen is why this practice is mostly missing in America. In my own experience with non-Jewish Southern American culture, such recognition is avoided because it gives rise to resentment and social disequilibrium amongst the collective. It is often desired, in those contexts, not to be seen, in the same way that one wants to avoid being accused of "Gettin' above your raisin'." Who is allowed to see whom can become a big problem ("Who you lookin' at?").

Even in old world contexts, this was often an issue for musicians, especially if they were from different ethnicities. I remember reading in Bright Balkan Morning how Rom musicians are studiously trained in the art of maintaining expressionless faces and lack of eye contact while performing for out-groups for just this reason. Cowan discusses the delicate ways the non-ethnic Greek musicians have to avoid the spotlight as well.

At any rate, there is still an overwhelming need for this sort of recognition, even amongst the most rootless and ninja-turtled of us, as is evident at rock shows when people scream at the mere mention of their local highway, "We just drove in on I-76!" The therapeutic or social value of this recognition is immense and our endless need for it drives so much of our behavior in all areas of life.

Zev has a wonderful account in his book about learning to phrase from watching Tarras dance. One got the sense of a very delicate balance: Was the dancer dancing to the music or was the musician musiking to the dance? Or was a third thing gently holding them both?

We may never get back to the elaborate, beautiful and exhausting layers of meaning that we had in the Old World, nor should we forget how confining they sometimes were. But there is a lot of low hanging fruit to be had in using music as a part of a process of seeing/being seen.

This is not being fancy or overintellectual- the opposite. We are setting our sites lower than complete historical recreation and focusing on something we can actually do. Whether we, as "secular" folks, choose to do this or not may depend on how comfortable we are divorcing these traditions from either their quasi-religious or grant-approved capital "A" Artistic contexts. Not something to take lightly.

At any rate, this all comes down, not to history or science, but to the differences I feel in playing klezmer vs. old time or other music. It’s a different sense of seeing. I wonder if others feel the same thing?

Part IV: Afterwords (Deeper History)

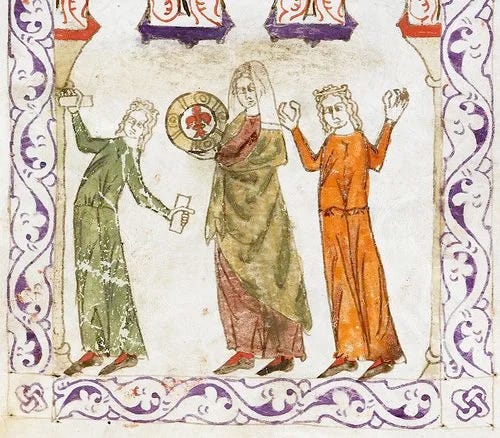

Afterword: The connection between hand gestures and music is actually super old. It has a name, cheironomy and it basically translates to an ancient form of conducting. Jews used it as an aid to sing/chant/read the Torah, just as Egyptians and Indians used it to read their holy texts. This has been documented in the European Jewish world up to the 11th century but persisted much longer amongst Yemenis. Like anything ancient and Egyptian, people attribute all sorts of magic to it, as I suspect Ted Gioia is fixing to do on his substack. I'm a sucker for this as much as anyone, but this kind of hand motion comes extremely naturally to anyone trying to communicate musical ideas and can be found at any children's music lesson anywhere on the planet. I suspect some klezmer folks have deeper takes on it, which I await.

Afterafterword: Zev distinguishes Jewish dance as distinct from its neighbors, specifically around expressivity. He defines the neighbors, appropriately enough in an Ashkenazic context, as Poles, Ukrainians, Hungarians, etc. and in that context he may be right. But he leaves out Greeks and only mentions them in his conclusion when he says Jewish dance might borrow from "exotic Balkan cultures" including "even the Greeks."

Consider this, a century before Hasidism. 1666, Constantinople:

[Sabbatai Zvi] did not hesitate to dance among his [Polish] visitors when moved to do so during their conversation of the fate of Polish Jewry. At the same time his behavior exhibited some of the traits usually associated with that of 18th or 19th century Hasidic rabbis; he would present his believers with a scarf, a morsel of food, or some other object which, by his very touch had become a kind of holy relic. We know that Sabbatai continued this practice long after his apostasy, for example when called to cure a sick believer in Adrianople. The narrative shows that the "Hasidic" style so often said to be specifically characteristic of Russian and Polish Jewry was perfectly possible a hundred years earlier in a completely different environment. Perhaps Sabbatai's gestures and behavior towards his believers were not even original with him... (Sholem)

I quoted this at length so I wouldn't be accused of squirrelyness. Sholem isn't saying that Zvi's dance was similar to Hasidic dancing (although Hasids still use the practice of interrupting conversation with singing and table pounding). Sholem seems to be specifically talking about the magic relic thing, not dancing, but Sholem had just finished recounting how Zvi had danced for a half hour, ecstatically enrapturing the rabbinic envoys from Lvov. I think it's entirely possible that a person born in Thessaloniki, who started a massive Ashkenazic Jewish cult that featured ecstatic and religious song and dance, might be given some consideration as a source for the expressive nature of Hasidic dance. See Sholem’s book on Zvi for more from this fascinating afternoon between the envoys from Lvov and Zvi in 1666.