WARNING: This is not the history of klezmer guitar, because I'm not sure there is such a thing and if there was, I don’t have the language or history skills to understand it. This is just notes I’ve gathered on the way.

The first thing one notices when looking into the history of klezmer guitar is… there aint much there. But, in the same way we can detect a black hole by the absence of light, the lack of a tradition can sometimes be revealing. In fact, the lack of klezmer guitar, for me, explains... everything.

Henry Worrall and American Primitive International Vernacular Middle Class Guitar

It's hard to know where to begin. Let's start in America. Specifically, Ohio right before the Civil War.

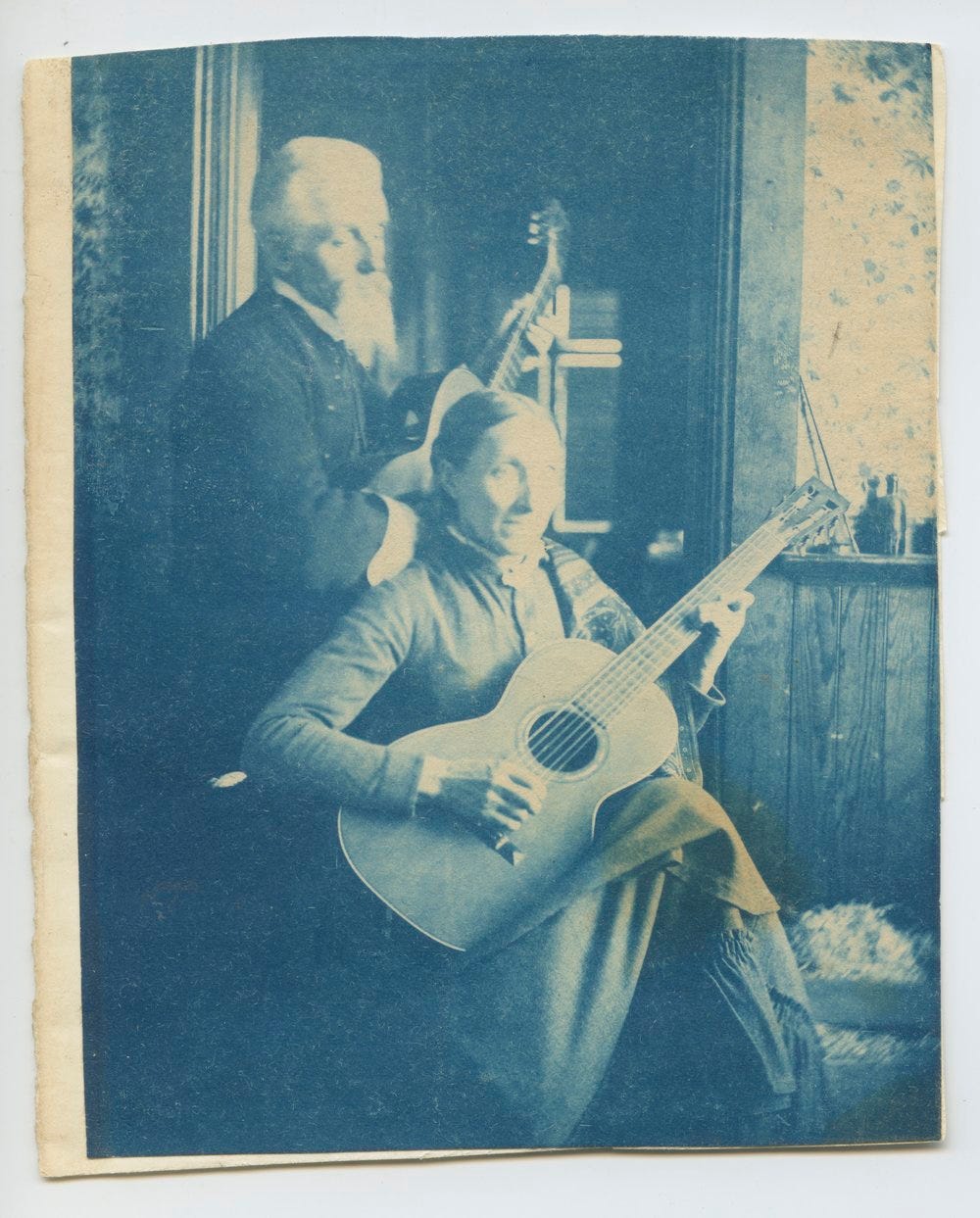

In 1855, a 30 year old musician and artist, English-born Henry Worrall was living in Ohio and teaching guitar at a women's college (remember that detail.) A mostly self taught guitarist, Henry Worrall played in open tunings. In order to teach this to others he composed and published compositions in this tuning. In 1856, he published an instrumental guitar tune called "Sebastopol" in an open D tuning to commemorate the battle of Sebastopol in the Crimean War. According to his own notes, the tune was "intended as an imitation of military music." He sold the tune for peanuts and his publisher went on to make a fortune from it. “Sebastopol,” and another tune he composed (maybe?! see footnote!) about a decade later called "Spanish Fandango,"1 became popular hits.

Through the power of print, Worrall's method transcended the powerful boundaries of gender, class and race at the time. His music could be found decades later in communities as diverse as black and white, women and men, rich and poor, and geographically, all over America, albeit adapted by the folk process. Spanish Fandango is still part of the core canon of "American" guitar tunes.

Worrall's song titles in his first publication included a handful of foreign tunes, interestingly many of which refer to Eastern Europe: the Russian Quadrille, Russian Melody and Hungarian Air. There is also a Cracovienne and a Sardinian Quadrille. It is not clear where he got these tunes although its not terribly surprising. A quick search reveals that piano music for tunes like this were floating around in the 1850s. It probably does prove that Worrall was connected, via music literacy, to an international world of popular "folk" music.

Worrall’s “Sebastopol” is unique amongst his place-based compositions in that it is describing not just a place, but an historical event or as he calls it, a “descriptive fantaisie.” Again, this is not entirely uncommon, there are fiddle tunes from the 19th century that are associated with historical battles, such as Bonaparte's Retreat. These tunes, like Sebastopol, mimetically and sonically duplicate the battle. In Worrall's case, he claimed to be imitating the music of a military band, a technique which requires banging on the guitar percussively.

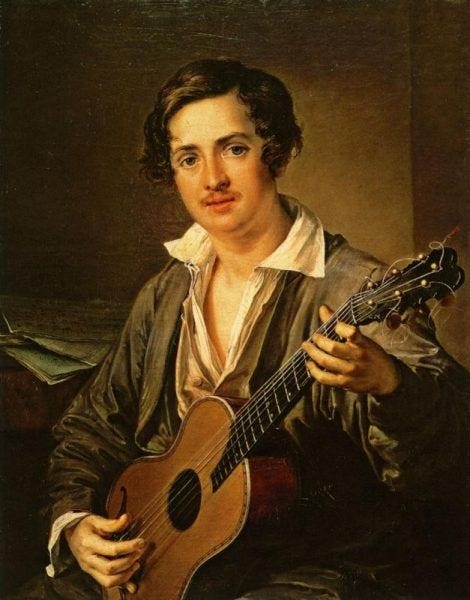

As it happens, at the time of the Battle of Sebastopol (1855), open tunings were at the height of their popularity in Russia. By then, there had already been at least a half century of published methods, journals and teachers who taught guitar in open tunings. The open tuned "Russian guitar" was actually its own species- a 7 string guitar tuned in open G. The first journal in Russia that was published for the 7 string guitar was published in 1799 and many others followed.

Hang on now, it gets a tad complicated: It is important to remember that at the same time, there was a parallel tradition of guitar that was also thriving in Russia, the so-called "standard" tuning 6 string method. There were sheets and methods aimed at these folks (known as "sixers" as opposed to the "seveners") too. These traditions, apparently, got along well into the 19th century, much as they would in America during the late 19th and early 20th, where many musicians recorded and were able to play proficiently in both tunings.

So by now, we should be asking “So What?” Why does any of this matter?

Transatlantic Guitar

The irascible independent scholar, Matanya Ophee paints a picture of a guitar diaspora that happened in the 18th century. The two methods (the 6ers and 7ers) found in Russia, he claims, stemmed from two distinct foreign traditions. One he says, derives from France and Italy, where 5 string instruments, tuned in 5ths, were played. The other, which would become the open tuning tradition, stemmed from Bohemian or Czech (or possibly even Vilna/Lithuanian) traditions, where a descendant of an English instrument was played, composed of 6 or 7 strings and tuned in thirds.

The central Europeans descended on Russia at the end of the 18th century, partially aided by expats and refugees fleeing the revolutions in those places at the time. From there, they cooked and developed these traditions. If we use Ophee’s guitar family tree, we can see that the guitar traditions that Worrall would have heard in 1825 England were kinfolk, via the Bohemian/English connection, to the same traditions one found in Russia at the same time.

These two traditions then evolved separately, but with important similarities. Here follows a fascinating and picturesque history of music in the 19th century, full of exotic harp-guitars and flamboyant virtuosi.

Long story short: (1), The guitar was unique in that it was aimed at a variety of classes. On both continents it was considered easy to learn (As Segovia says, "The guitar is the easiest instrument to learn to play badly") and was deliberately used an instrument to play folk tunes. (2) It was assumed that the guitar was an instrument for indoor use, as in the salon or parlor. This is important because, as an indoor instrument, it was available to women (remember Worrall taught music in a women’s college. Internationally, women, such as Maybelle Carter, Lydia Mendoza, Memphis Minnie, Elizabeth Cotten and others would have important roles in the guitar’s history, esp when compared to other instruments.)

And it worked! The guitar was played, by women, men, rich and poor all over, for their own entertainment and professionally ever since.

Insert here the golden age of the international open tuned guitar, where a woman from Kansas and a woman from Odessa might have been able to sit down and jam on some tunes thanks to 18th century Bohemia.

Meanwhile: In addition to the influence of these published methods, we should not forget that other traditions, full of more vernacular instruments, like banjos, balalaikas, cobzas, baglamas and who knows what else, were also percolating internationally. These instruments often featured open tunings and their story needs to be told as well. But not now.

The Bad Guy

But this golden age ended and the villain’s name was Andres Segovia. In the East, this all came crashing down in the 1930s, when Andres Segovia, that detester of “bad” guitar, visited Russia. During his extended stay, he viciously disparaged the 7 string as hopelessly inferior:

"Dilettantes were always adding extra strings, being content with finger picking several trivial motives, instead of serious work on the instrument’s technique...All the possibilities of playing on this instrument are included in the six strings." After Segovia, the 7-string fell into severe decline in Russia. As Ophee says, his campaign to end the 7 string guitar was “eminently successful.”

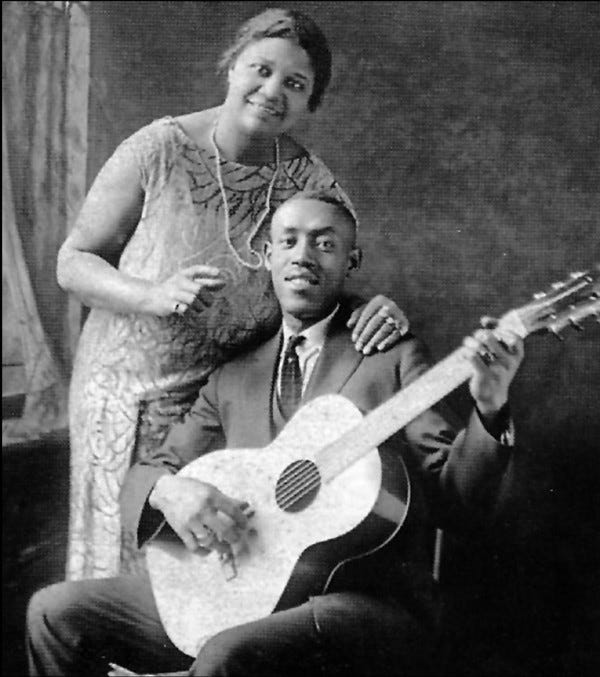

On the other side of the Atlantic, the open-tuned and fingerpicked guitar flourished. Seven years before Segovia's comments, an African-American and Kentucky-born guitar player named Sylvester Weaver recorded Guitar Rag, the first recorded slide blues on guitar, done in Worrall’s Sebastopol tuning. This gives us a snapshot of where the tradition was at this time. It wasn't the first record in this tuning, but it spotlit the guitar and used some Worrall-esque motifs. Around the time Segovia killed the open-tuned guitar in Russia, it was in the middle of what would be a long career in American blues and country.

So who was right? Is it a good thing because it’s democratically accessible or is it a bad thing because “It’s the easiest instrument to learn how to play badly”? In America, There was no Segovian counter-revolution (there were attempts but they didn’t win out), which is why someone like me, who grew up on ninja turtles and Froot Loops, could learn about open tunings by folks who still used the terms "Sebastopol" and "Spanish." I was able, in my lifetime, to have living contact with one of the women, Etta Baker, who grew up in this tradition.

In America we find an actual example of “what could have been?” and it shows clearly that Segovia can go stuff it. Due to a variety of happy accidents, we have a ton of recordings from the American experience and they show an experimental, innovative approach to guitar that matches or exceeds the best of any boring classical performance.

What About Klezmer?

My grandfather played Yiddish, Russian, Ukrainian and American folk music by ear on a six-string guitar with an open tuning he had adapted from the Russian seven-string instrument. Using his thumb to finger bass lines, he accompanied balalaika players, mandolinists, and singers, including my step-gradmother, Pauline. It is quite likely that his father- who according to my father had been a violinist- was a klezmer.

That’s Joel Rubin. The seven string guitar was marginalized in the East by the 1930s, but was found in Jewish Eastern Europe before that. Tarras played guitar before he touched a clarinet. But, as we will see later, unlike other genres, including Eastern European ones, guitar wasn’t adapted by Jews to klezmer music. To understand why we have to go deeper into the history of both guitar and klezmer. Next!

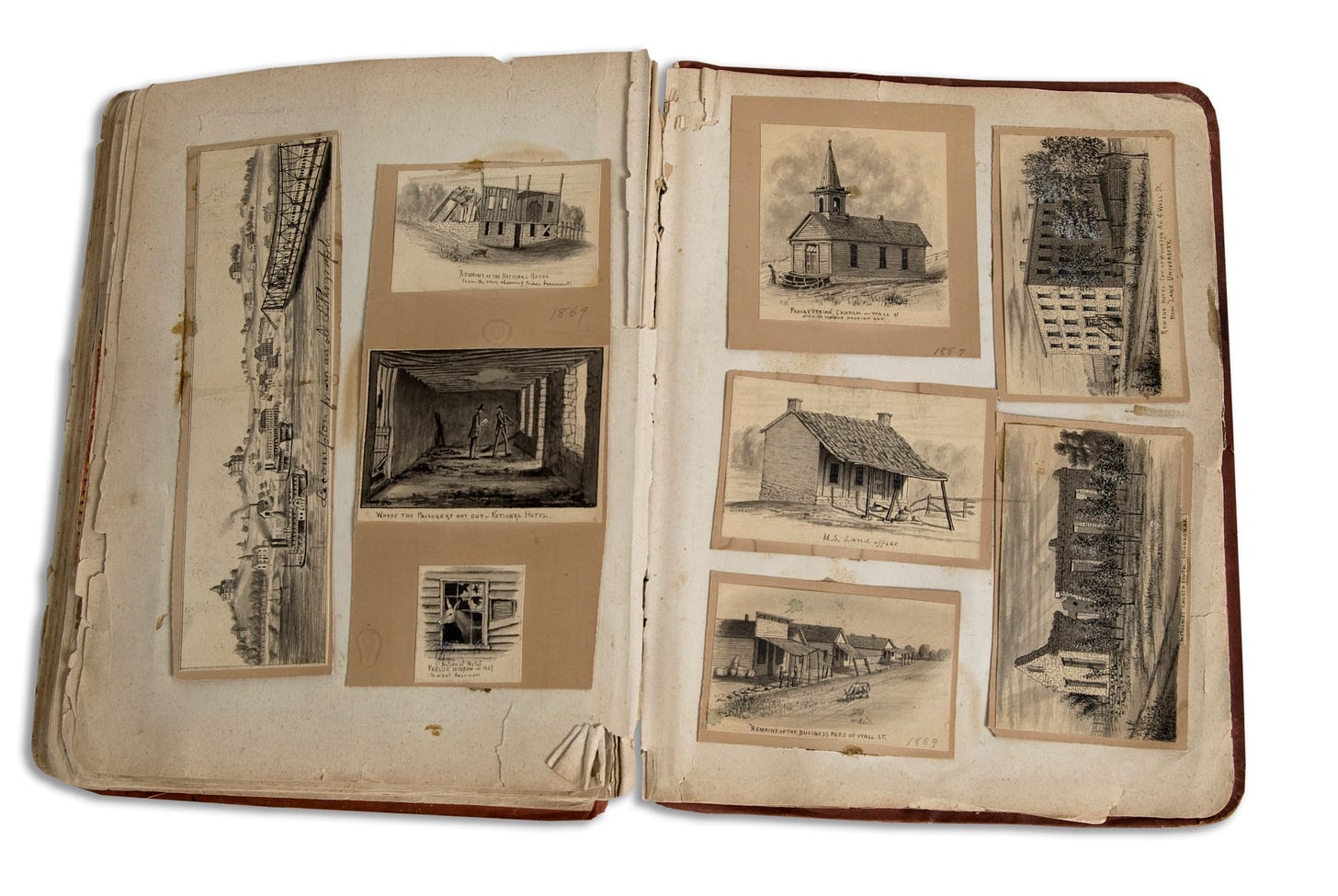

Afterword: Henry Worrall deserves his own post, as his legacy is much more than what I summarized above. A few details and then a dramatic conclusion for now will have to suffice:

Dang it if he didn’t maybe play an early version of the tsimbl too! Worrall “made one of his characteristic speeches...and played on his wood and straw piano.” What that means we’ll never know, but it is remarkably similar to the descriptions of Gusikov’s instrument “On wood and straw, from wood and straw he teases sounds, sounds of the innermost melancholy, sounds of great pathos .... From wood and straw he extracts the most exquisite vibrations, the most sensitive oscillations, the softness of elegy.” He also seemed to have invented and played his own instruments.

He was a sketchbook guy, who helped found the Cincinnati Sketch Club. He also formed a sketch club in Topeka and notably, opened its membership to women as well.

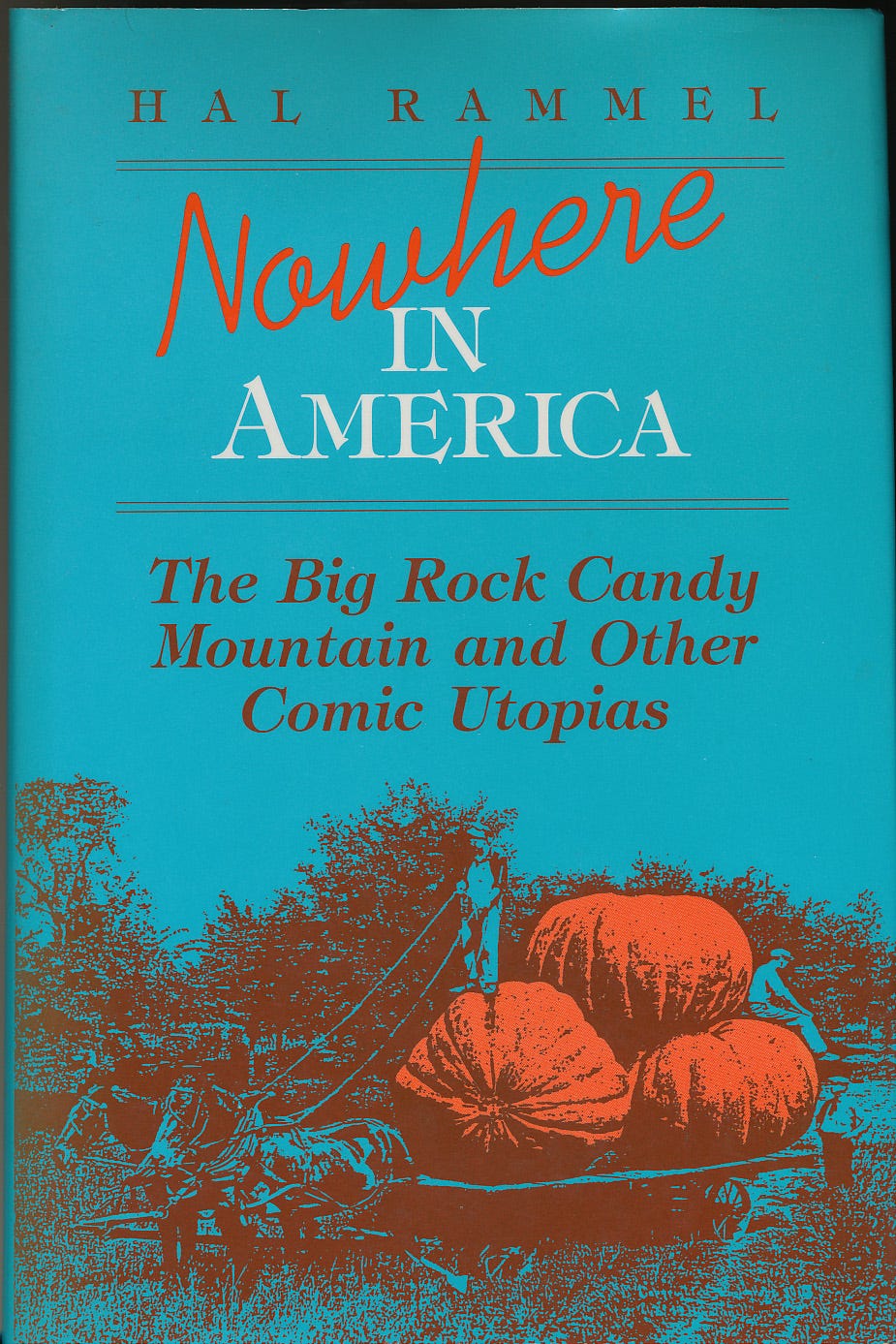

He was a crop art innovator.

Responsible for decorating both the railroad and the Kansas portions [of the Philadelphia 1876 Centennial World’s Fair], Worrall diligently collected crops from all over the state, shipped them to Philadelphia, and covered the walls with stalks of corn, filled glass columns with oats and rye, and constructed Corinthian capitals out of grain heads. In the center of the rotunda, he hung a crop-art version of the Liberty Bell. More than 8' high, the bell was fashioned of broomcorn, millet, and wheat; the clapper was a huge gourd. On the back wall, sunburst rays of cotton and corn surrounded grain-art versions of the state seal and a map of the Kansas counties. In the fall, Worrall closed the exhibit for two days and astounded everyone by reopening with a new feature—a model of the U.S. Capitol, 20' high and covered with apples. No other state had troubled even to renew its exhibits with fresh produce; Worrall had created a whole new display…

Worrall did not invent crop art, but there were few contemporary precedents for what he created in Philadelphia. The 1851 London Crystal Palace’s tins of meat and champagne bottles stacked in pyramids and the 1853 New York Crystal Palace’s sugar-paste model of Greenwich Village were single exhibits, not the integrated whole that Worrall designed for the Centennial Exposition. Wherever he got the idea—from European harvest festivals or seventeenth-century Cockaigne arches, from Renaissance banquet centerpieces, rustic folk art, or state-fair fruit pyramids—Henry Worrall became one of the chief nineteenth-century practitioners of the art.

How can you not have sympathy for this guy? His corn art is a perfect crossover with the transforming plants we’ll find in the series on Ornament (forthcoming) as well as the Willy Wonka-esque edible Hard Rock Candy mountain that would be at home in the Hobo series.

Sadly, this artist-musician visionary was, behind his cheery disposition, no stranger to the darker side of life, having twice tried to kill himself, although we know nothing more than that.

It’s no accident that the character of Worrall strikes such a chord with us (I didn’t even mention his acting parodies or his “racy… crayon and musical performances.”) He was the prototype of an Americanized version of… us! His salon-room guitar playing, his sketchbook clubs, his caricatures and local dramas, his regional interests- they all point to a democratic, homegrown type of culture that would come to be synonymous with a certain strain of American culture. We call it folk (I prefer “social”) and it is a term much maligned these days for its nationalistic associations, but Worrall’s folk was not nationalistic (his repertoire was quite cosmopolitan). It was funky, weird and self consciously artistic without being elite or Arty. It was aimed and informed by the vernacular but never volkish.

In Europe the guitar was an accessory to the upper and middle classes; it was introduced to America in the colonial and Federalist periods with that pedigree. In the United States it had yet to develop any folk associations and was only beginning to acquire popular ones. In the Romantic spirit of dialectic synthesis, Worrall was among the first to associate this cultivated European instrument with the robust, diversified vernacular American culture of his day. Henry Worrall, Anglo-American Guitarist

Apparently, everyone was writing Spanish Fandango back then. See this article and their lone footnote for more info. Justin Holland, a very interesting guitarist Af-Am freemason and political fighter in his own right, also penned it (also in “spanish”, open G.) The blog I linked cites an article by Peter Danner about a 1836/8 version of Spanish Fandango. You can read that article here: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=sbs