We saw, in a previous essay, how two guitar traditions were percolating throughout Eastern Europe in the 19th century. One, featuring open tunings, of English/Bohemian origin, and the other, with tuning more mandolin/violin like, that came from Italy and France.

But there's one more. And it's a doozy.

I'm talking about the Carpathian zongora.

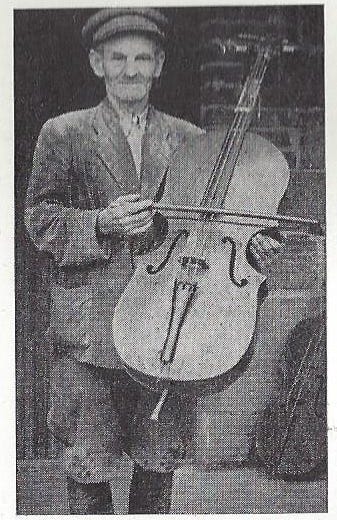

The zongora (translated, “piano”) is played, well, I mean, it's... oh heck, just look at the picture:

An expert on the intersection of this guitar style and Jewish culture from this region is Bob Cohen, who I owe many thanks to (all mistakes mine) for documenting this tradition. Here’s a great video he took of this style. I remember reading somewhere, that he said the local lautari/Gypsy folks distinctly said this style was not found in klezmer.

Oh well, another dead end, right?

Not quite. One of the mysteries of the zongora is why it is played in the awkward position that it is. Wouldn't it be more comfortable held across the lap like a normal guitar? The up and down stroke is objectively less awkward for humans than the side to side one. So why side to side?

There is another bizarre instrument haunting the Carpathians that answers the question. The basy. The basy looks like an ersatz cello or bass. Maybe someone somewhere saw a bass or a cello and then went home to make one. When seen as a cello, it is obviously inferior, and one is tempted to laugh. But when looked at functionally, it very much fills the role of a drone-y rhythm, a role that was already in the music and performed by the bagpipe. It functions more like a rhythm instrument than anything, and, as such, the important dynamic is not the notes it can produce but the vigorous side to side bowing stroke, creating a wonderfully earthy, harmonically primitive, rhythm. Some ethnomusicologists have even gone on to suggest that the pushing and pulling of the bow across the basy resonates with peasant patterns of agriculture (see Czekanowski, Polish Folk Music). A bit too much of a stretch for me, but what do I know?

The zongora’s side to side stroke makes sense when seen in the context of the basy. The strings are not fretted with the left hand like a normal guitar/cello but played roughly, often in one chord only. Even when they are fretted, the notes are not the show. The zongora is a poor man's basy, and the basy is a poor man's cello, but not really- actually a poor man’s bagpipe! See it’s all very simple!

This would also explain why the zongora often has just 3 or 4 strings.

The association with the bagpipe and the drone is crucial. It was noticed by Chopin during his 19th century research on Polish fiddling traditions. The agricultural connection to basy bowing might be a bridge too far for me, but the bagpipe’s symbolic resonances go deep and will be explored later.

But again, whither klezmer? Even if we allow this connection between the zongora and the basy made by some armchair internet user in America, we still don't have any recordings or other evidence of basy used in klezmer ensembles.

Except one:

This picture depicts a Carpathian band made up of Jews and local lautari(?) and we can clearly see the basy. Was this basy played in the same style we hear from Polish village bands? Don’t know. Did this band play klezmer? Probably. When seen in the proper context, the question boils down not to historical quibbles about who used what, but how the bass functioned in these ensembles. When they played klezmer, did it keep that lingering trace of the bagpipe drone?

Not so fast. There is one important difference between the zongora and the basy that gets to the heart of why there is no klezmer guitar. The zongora, at least in rural non-Jewish Carpathian culture, is often played by the fiddler's wife, and this echoes a centuries long association of the guitar with women in general. This practice would be very strange indeed to the religiously conservative Jews of that area (See Sendrey too on the lack of Jewish co-ed family bands going way back). And besides, we already had a sekund (or rhythm fiddle). In the picture above we see not one but three fiddlers. As we’ll see later, when the bagpipe was discarded for the fiddle, it coincided with a status upgrade for musicians. Bagpipe, old, violin, fancy. Guitar, in any form, would probably be seen as a downgrade, maybe especially if it was associated with bagpipes.

This sensitivity to status was very real and explains one of the most bizarre phenomenons in the entire traditional music world, the Fake Real accordion. In Polish villages, piano accordions were considered higher status than button ones, so this is a button accordion disguised as a piano accordion.

The zongora’s association with women, amateurishness and the lower status of drone instruments may have explained why it came close, but no cigar, to being the klezmer guitar. Plus I’m having fun, as the zongora never really spread beyond its geographical origins in any community.

Two last loose ties need to be at least addressed before we leave that region.

One, the cobza/koboz, an instrument vaguely similar to the zongora, was a plucked stringed instrument which we have evidence was used by Jews and even klezmorim (Tarras was learning it back in his guitar days as well). I definitely hope to get to that, but not sure I can add anything that Bob Cohen hasn’t already. Again, never recorded, never depicted (as far as I can tell).

Two, what was the role of the Lautari, a group of folks literally named after the lute, in Jewish musicians’ ideas about the instrument? Obviously a huge question.