Before Ecstasy

We moderns tend to think early people were profoundly and authentically musical just as we tend to think they were profoundly religious, spiritually “in tune” and superstitious. But that may not be the case.1

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, in her study of one of the last nomadic hunter/gatherer societies paints a picture of a group of people who have little need for religion. Their gods aren't transcendent, moral or all powerful; they are just kinda weird people who live on earth and look like us. Although the tribespeople sometimes construct elaborate stories about natural phenomena, such as the stars being cosmic ant-lions, they also know that we can't see them in the daytime because... it's too bright out.

What is thunder? It's thunder, just as a rock is a rock or a tree is a tree... No superstitious construct was needed to explain these phenomena…. True there are plenty of superstitious people in the world, but they live in agricultural or industrial societies, removed from the natural world and afraid of it.

Morris Berman, in his study of nomadic spirituality, found similar conclusions. He argues that..

…Sacred experience did exist in the paleolithic but… it was not the sort envisioned by writers such as Eliade. Instead what was dominant was a more horizontal2 spirituality, a persistent “secular” tradition that is a lot less exotic but that because of its obviousness (and our own fascination with the exotic) has escaped our attention.

Among his evidence is cave art, which, as is widely noted, is oddly realistic.3 Thomas and Berman suggest that paleolithic life simply needed good ol’ common sense too much to get carried away by fanciful metaphysics.

Berman, echoing Thomas’ comment on superstition, says the need for religious hooey emerges not with the paleolithic but with the neolithic and the beginnings of social hierarchy. In other words, social hierarchy created stress and that, in turn created a need for transcendence in the form of ecstasy. These ecstatic forms then evolved, starting as democratic free-for-alls, then freelanced into differing types of shamanism, and then monopolized by priestly castes. Each stage, overall, becomes more centralized and less democratically ecstatic.

What is the musical equivalent of this prehistoric low-key spirituality or the naturalistic rock art? We will never know, of course. But the timbral echoes that Süzükei described, with their horizontal realism, seem to be a close parallel.

If we examine the worldview that existed before the crisis of hierarchy and anxiety, what we find is not ecstasy, but equanimity. Berman calls this state “paradox” or, as he says, the experience of “space.”

It is not characterized by a search for “meaning,” an insistence or hope that the world be this way or that. It simply accepts the world as it presents itself…

This is not hippified bliss, nor is it bovine “dullardism”, both of which are reactions to the stress of life in hierarchical societies. Gatherer/hunter spirituality, if it can be called that, can be best imagined simply as a state of non-resentment: “One does not deal with alienation so much as live with it.”

Berman’s inclusion of spatial dynamics as a key aspect of this state is curious. Written a decade before Süzükei’s work, his mention of it in this context has some parallels.

I ran across one description of this state in Field’s A Life of One’s Own, in which she refers to it as wide, as opposed to narrow attention… this mindset is actually well known in the anthropological literature. 4

He also cites Ortega y Gasset from Meditations on Hunting:

It is a universal attention, which does not inscribe itself on any point and tries to be on all points. There is a magnificent term for this, [namely]… alertness… Only the hunter, imitating the perpetual alertness of the wild animal… sees everything.

If you've ever foraged mushrooms or anything else in the wild, you know that this wide attention5 is also essential for gatherers as well.

Berman's spacey "paradox" connects timbral listening to a different way of experiencing the world. It is oddly similar to Baldwin's "ironic tenacity," which also emerged from a sensory experience of contradictions. In addition, Baldwin's ironies were also a rejection of the ascent into metaphysical heights or meaning in favor of a descent into the everyday. I don’t think they are identical6 but both seem to be exploring the same, still mostly uncharted, territory from different trailheads.

Cool

What does equanimity sound like? As we often have in this series, we look to the nomadic pastoral for clues.

In America, the idealized pastoral role is projected on to the Cowboy.7 Like the examples above, cowboys are imagined as earthy practical types who are not given to a lot of metaphysical woo. They are often depicted as "cool" and collected, as opposed to the pitchfork wielding agricultural rabble. They look unattentive; motionless, with their feet up8, a piece of straw in their mouth and their hat pulled over their eyes, but actually we learn that they are in a profound state of volumetric attention and alert to everything going on.

Of course, “cool” first emerges in African-American culture, another popular target for the dominating classes’ projections. As with the Cowboy, “cool” in this context also means attentive but non-reactive, and in that sense, self-controlled or unowned. To be cool is to reject the status society has determined for you. This often manifests itself in minor acts of rebellion, i.e. showing up late9, rejecting expected social roles, even wearing sunglasses indoors at night, etc. 10

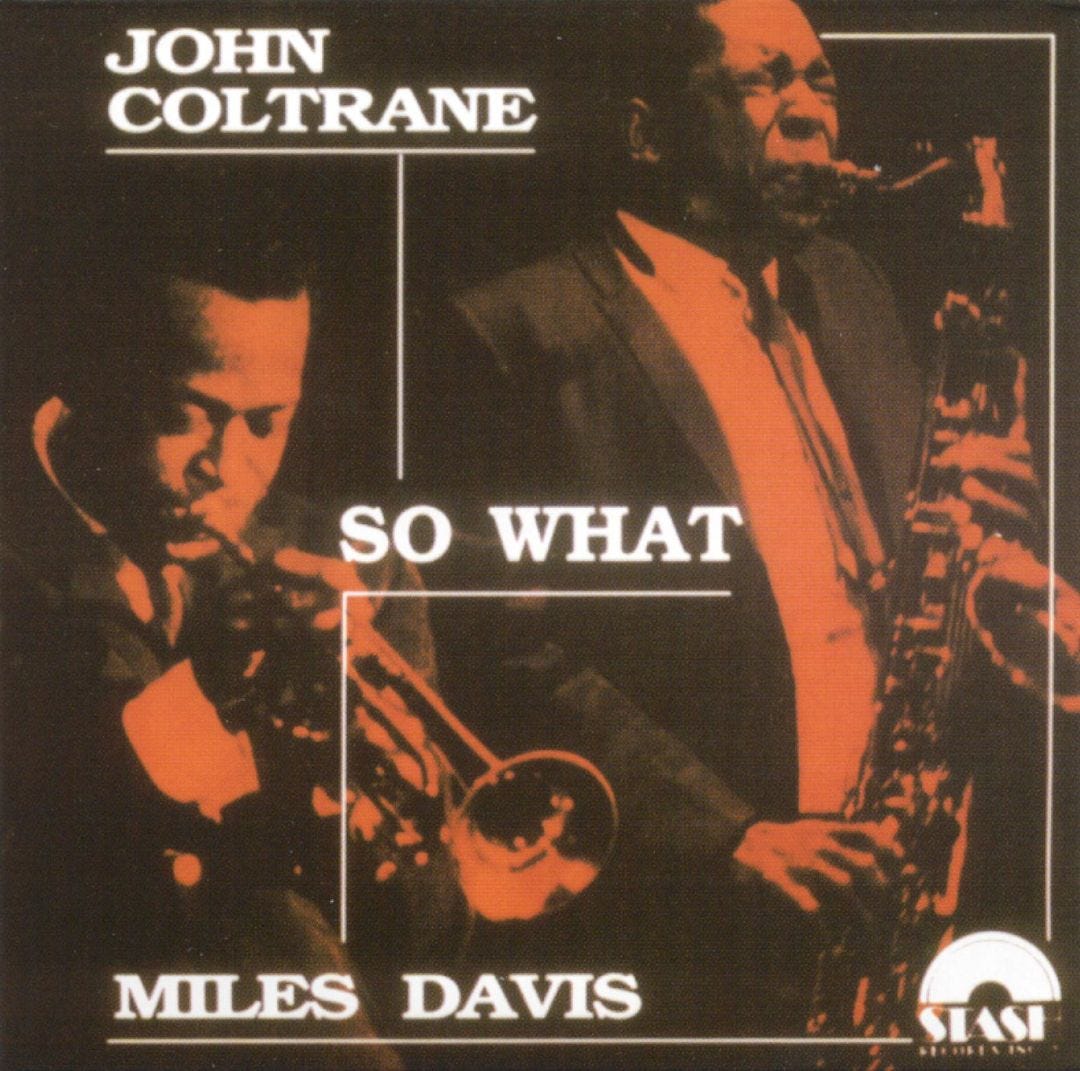

As with our examples of cool above, the sort of music that equanimity creates leans heavily on the timbral. Consider Miles Davis circa Kind of Blue or the flowing rhythms and woozy shimmering harmonies of cowboy music.11

These are examples of how timbral listening, and the worldview it comes from, manifest in contemporary music. They are also examples of the manic hall-of-mirrors type projection that surrounds the timbral and those populations who live outside the gates of sedentary society. We have to tread lightly because real people and social groups are implicated, but we can’t ignore that our need to project in these ways reveals long-standing and dangerous cracks in our civilizational foundation.

The freedom found, either real or imagined, outside the gates of sedentary society is an important reminder that something is missing, but it cannot be our goal. Our culture is just the latest in a centuries-long dance with these powerful often contradictory forces, and we continue to evolve.

Below Timbre

So far, we've discussed timbre as not a solo, but a duet. But it might be a trio. It's not just the call or the response that matters. There’s also a third player- silence.

In the first post, I mentioned that timbre was the last layer on our archeological dig... “sorta." Silence, without which timbre is impossible and vice versa, is that final layer, deeply enmeshed with timbre.

In the 1940s concrete musician pioneer Pierre Schaeffer experimented with cutting off the initial few microseconds on a recording of a bell sound. He found that without this "attack," the timbre of the bell was cloaked. Hence, a key aspect of timbre are these first few microseconds…

Taking this a step further, I would argue that silences have timbre, not in the physical, spectral sense, but insofar as their effect is determined, like the timbre of physical sound, as much by how they are initiated and ended "as their substance." Routledge

Again, this is not fancy-pants intellectualization but practical everyday stuff. Although this phenomenon is hard to capture in any media, this video does a brilliant job of letting the video go on long enough to capture how not all silences are the same.

Timbre allows us to hear silence (something Süzükei mentions as well in her study of Tuvan singers). As our spatial awareness grows into that silence, time slows down, pushing our attention into very strange territory indeed.12 This is another entry point into the same region explored by Berman and Baldwin.

Conclusion: So What?

In this series, I’ve tried to show that the aspects of music, from melody to ornament to phrasing and now timbre/silence, aren’t self-contained, vacuum-wrapped commodities, but are meaningful to the extent that they connect music to a broader context. Ornament connects melody to us by predigesting it for us, phrasing connects the music to our bodies and to the social, and now, timbre/silence connects us to pre-bodily experiences of the existentially cosmic.13 Ok great, but what does this mean for you and that instrument on your lap?

The timbral worldview is only useful in small doses. Otherwise it becomes unlistenable and we purge it from our experience. It is also not always necessary. Sometimes we just connect on more bodily or social levels. But when we need it, we find that melody and the other aspects of music are useful in lulling us into a state where we can be receptive to those one or two moments when timbral awareness can break through. To do this requires thought and intuition as to the right set and setting; for instance, what is the ideal size of the band, type of venue, can it work with an audience of strangers or does it need the warmth of acquaintances? More research is needed.

Finally, and this is most important- it might sound like I’m suggesting that timbre is sorta psychedelic. Possibly- after all, timbral listening can take us out of our everyday consciousness. But unlike almost all psychedelic discourse these days, let’s constantly remind ourselves, as Baldwin did, that while ecstasy is necessary for civilized life, equanimity is much less discussed but may be the real source and goal that timbre reveals.14

Next: From the Pyramid to the Campfire: Final Thoughts

“The idea that primitive man is by nature deeply religious is nonsense. . . . The illusion that all primitives are pious, credulous and subject to the teaching of priests or magicians has probably done even more to impede our understanding of our own civilisation than it has confused the interpretations of archaeologists dealing with the dead past.” Mary Douglas Natural Symbols

Buber “The tradition of the campfire faces that of the pyramid” said in the context of the fluid charismatic Jewish nomadic societies vs fixed state priestly Egyptian society. The pastoral ramifications of Exodus are very twisted and complicated, with no easy conclusions. However, the verticality of the Egyptian religion and social structure is hard to deny. Berman makes a big deal of the the horizontal (valley) vs. the vertical (mountain) as does James Hillman (see Peaks and Vales). I communicated briefly with Morris Berman years ago. He told me in no uncertain terms he disliked any comparison with Hillman. At any rate, the bottom line is that the mountain/valley business is a crazy nexus where music, spirituality, anthropological politics and psychology all meet and signify amongst each other.

David Wengrow comes to a similar conclusion about this rock art and takes on the many interpretations of the one transcendent figure often cited as a “shaman” or god in rock art.

Another strange parallel between Berman and Suzukei is the observation that this spatial awareness is accompanied by physical stillness. Suzukei mentions that many timbral singers/musicians produce the sound with an almost magical lack of observable motion.

The role of wide vs narrow attention in music has lots of implications for spirituality and anthropology. You could look at different religious traditions, many of which started to emerge at the same time, as ways to maintain or cultivate nomadic states of attention in the context of sedentary cultures. Too much to go into here. “Cool is a form of Negro Zen.” (Jelani Cobb, 2009)

Most notably, Baldwin’s ironic tenacity takes place in social and musical situations whereas Berman’s does not.

We have to keep in mind that the cowboy, as pastoral nomadics, are not what they seem. They are always the object of our projections on to them. But those projections, though not necessarily “true” in describing cowboys, are true in the sense that they tell us important things about ourselves.

Ok, you think I’m crazy, but there’s actually a fascinating history of reclining. I’ll say no more!

We see this behavior in various musicians, including Naftule Brandwein, who, as we’ve seen in other posts, shares other aspects of this anti-normative behavior.

Cool emerges just as the primitive rebels we saw in earlier posts start to die out. It becomes the individualist iteration of this impulse (the other wing becoming collective “not-primitive” rebellion i.e. socialist revolution). The political crossroads this creates will have to remained unexamined for now but is critical- think of the decidely uncool and untimbral music of the collectivist Pete Seeger types vs. Dylan’s timbral apolitical individualism. This should be a reminder that the timbral, like the anarchist politics of the hunter/gatherer should not be easily idealized, but needs to be historicized to see how they manifest in our social lives.

Cool Hand Luke’s Plastic Jesus is a remarkably weird anti-religious, even maskilic song.

Expansion into bigger and bigger spaces slows down temporal events, to the degree that a single vibration or rotation, of our planet takes a whole day, and that of a galaxy, millions of years… dematerializing and eroding the integrity of singers and song.” Jocelyn Godwin via Plantegna

All of these are done in cultural ways.

See also negative capability, another expedition into this same territory that Baldwin and Berman trekked through.